Recently, I reviewed Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life, using a traditional style of storytelling, instead of a typical book review, which, given the stature of the man among his disciples, would have sounded totally inappropriate. I called him prophet because, quite frankly, I liked the idea of a cold country on the outer edges of history and classical civilization producing its own apostle. A Middle Eastern prophet, an Asian guru, or some Mesoamerican god would simply not fit the bill for an age in which the powers of cyberspace seem to have eclipsed those of the natural world. A clinical psychologist who spreads the word through YouTube and tweets nonstop has a far better profile than a camel herder. New times require new leaders.

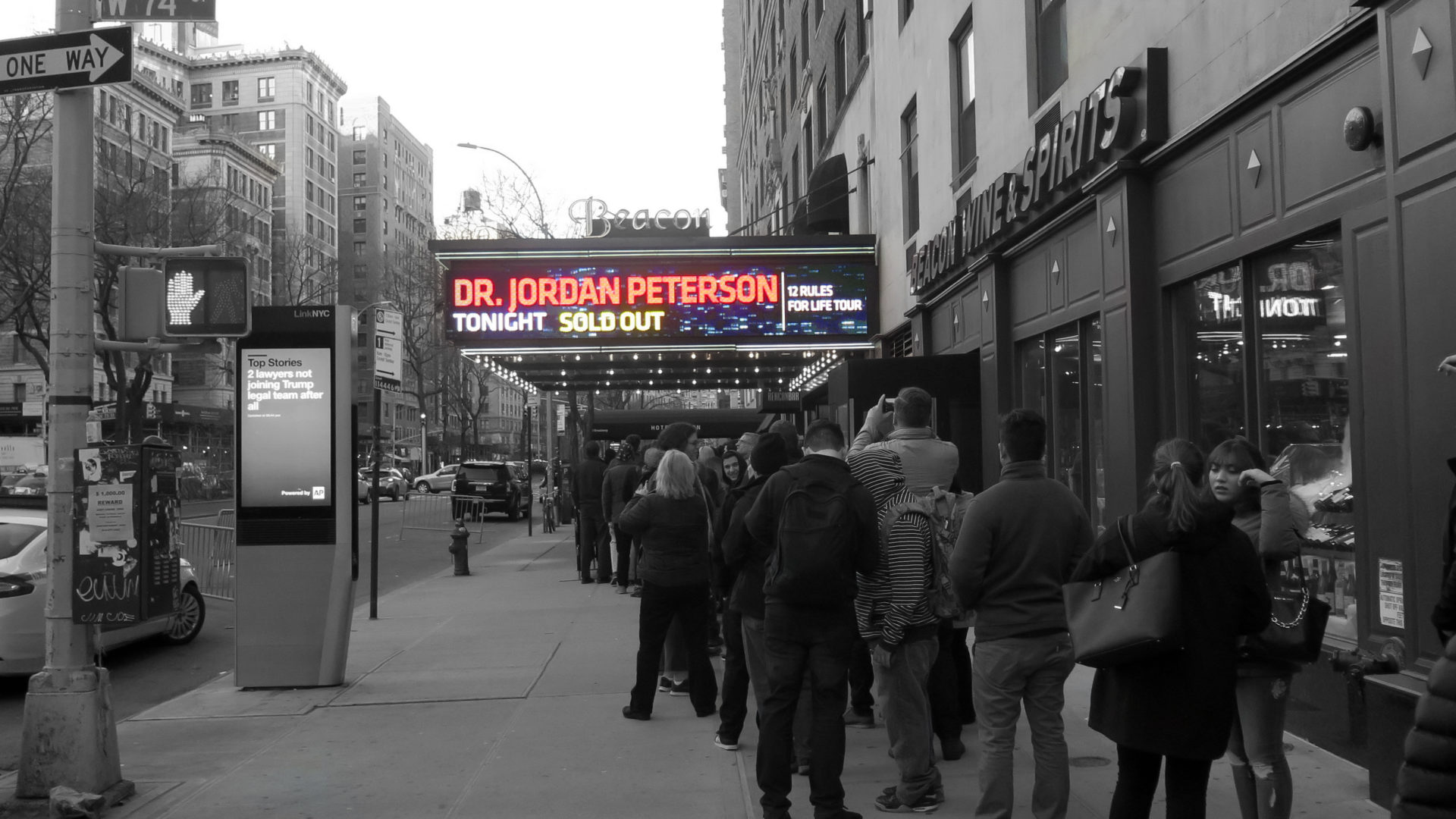

My review of Peterson’s book landed me in a panel about the man and his work before I flew down to New York City (from my home in Portland, Maine) to see him in what seems to be the opening salvo of a book tour that will take him around North America and the world. The Beacon Theater on the Upper West Side of Manhattan was the venue chosen for this historic moment and sold out event. Long lines, mostly of white, middle-class-looking people, including women, stretched on both sides of the main entrance. Security was tight.

After much waiting, Dave Rubin, the comedian and host of The Rubin Report on YouTube, appeared on stage to open the act and wait till people got settled before lifting the curtains on Peterson and allowing the man himself to walk on stage. As you could see in this bad video I took with my small camera, the people in the theater leapt with joy while Peterson himself seems to be amazed at the whole thing. As soon as the thrill of the live encounter subsided for a moment, the professional author proceeded to explain his rules, unpacking each one, as he does in his book, with numerous examples and observations, until he ran out of time. He was able to cover only six rules before Rubin came back on stage to rescue him and open the floor to questions. The hour was quickly approaching 10 pm and long lines of people had formed to ask questions. My wife, son and I just called it a night and left. The show was over for us.

In the course of his presentation, Peterson gave a nod to Karl Marx for highlighting the inequality that is an unavoidable feature of the capitalist economic system but instantly reminded us that there are no capitalists in lobster societies; he emphasized, yet again, that life is fundamentally tragic; bemoaned our propensity to waste time and resources (using a Fordist example to illustrate Ben Franklin’s old adage that time is money) by not having a well-defined aim; warned us of the consequences of not standing up to bullies; and advised us to avoid false friends. We shouldn’t forget to be kind to ourselves (or worry too much about the bogus charge of narcissism, unless it rises to pathological levels) and remember that the descriptor nice is not only a meaningless adjective but is actually a “low-end virtue.”

There was a revelatory moment during Peterson’s presentation when both he and the audience realized why he has attained such a semi-divine status among his fans: Peterson expresses what they know in their hearts and minds but cannot articulate with the precision and supporting data he marshals so flawlessly. Armed with such recognition, the Canadian professor paced on stage like an impatient preacher running out of time. He was on an impossible mission to save lives and rescue the world from damnation.

As I had assumed in my review, Peterson’s show is not a discussion of ideas but a sermon delivered to a new congregation that wants its truth wrapped in the scientific method and couched in unassailable data. A historical consciousness is missing from Peterson’s presentation, despite repeated appeals to psychologists, select literary works, ancient scripture and the like. When he uses the example of school shootings in America and the nihilistic worldviews of the men behind them, he never pauses to wonder whether he is talking about a distinctly U.S. phenomenon (one that is not even Canadian) or about human nature in general. Peterson would make a comment about accepting the tragedy of existence and follow it up by saying that the West got it right, as if this were a logical sequitir. His repeated desire to vindicate the West comes across more like sloganeering designed to appeal to people who are justifiably tired of hearing politically correct cultural elites denounce their heritage than as a considered reflection on the meaning of the West. The latter, as a geographically and culturally delineated area, is so amorphous as to have become a meaningless category. By some criteria, South Korea, Japan, and China are more Western than Spain and Italy.

If Peterson wants to defend the philosophy of the European Enlightenment (on which his scholarship is, ultimately, based), then he should spend some time explaining that to his followers. I myself champion the tenets of the Enlightenment, but such tenets are a mixed bag of views that cannot be reduced to, say, the unconditional praise of capitalism, even if the latter economic model has lifted untold lives out of poverty and reduced starvation in most of the world today. Capitalism, in Marx’s definition, is not just a system of profit making but also one of social relations, and it is in this aspect that it falters miserably. Furthermore, why would a man who never tires of reminding us of the tragic dimension of existence see life in such a utilitarian fashion? Counting wasted hours in dollars, measuring progress by whether Africans have cell phones, or simply tracking the rise of per capita income is not enough and says precious little about the state of the human condition in our world of abundant riches. Many wealthy nations are suffering in their opulence, while many poor Africans or Latinos are happy-go-lucky despite suffering endless economic deprivations. Besides, since when did prophets approach the crisis of meaning by using dollar figures and better living standards to illustrate their point?

If this were an intellectual forum, Peterson and I would have much to discuss; but, as I have indicated, this is something that is much bigger than my views on the matter. The man is doing God’s work by embracing the masses hungering for meaning and lifting their spirits by arguments that often make sense. I see in him a kind and caring man who truly feels the pain of others. If the title of prophet seems exaggerated (and, by the way, there was absolutely no satire in my review of his book, only a style befitting the occasion), he definitely belongs to the prophetic tradition of healers and caregivers. We absolutely need more Petersons in the world, not less.

Yet, after attending his event at the Beacon, I am now worried about the commercialization of Peterson and his message. He seems to have turned into an industry and his talk looked and sometimes sounded more like a stand-up comedy routine than an academic lecture or a holy man’s message. Watching Peterson on stage, with his head-worn mic, gave me the unsettling vision of what happens to saints and apostles in the late-capitalist phase. Through the magical powers of entertainment, Peterson and his sacred message were dissolved into yet another spectacle. If he isn’t careful in managing his business relationships well, his 12 rules for life will eventually be eclipsed by the only value that matters to the masters of finance. This is a conundrum only the likes of Noam Chomsky (a prophet systematically shunned by capitalists and the mainstream media) have been able to avoid. After all, it is Peterson himself who reminded us of the Christian warning: “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?”

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.