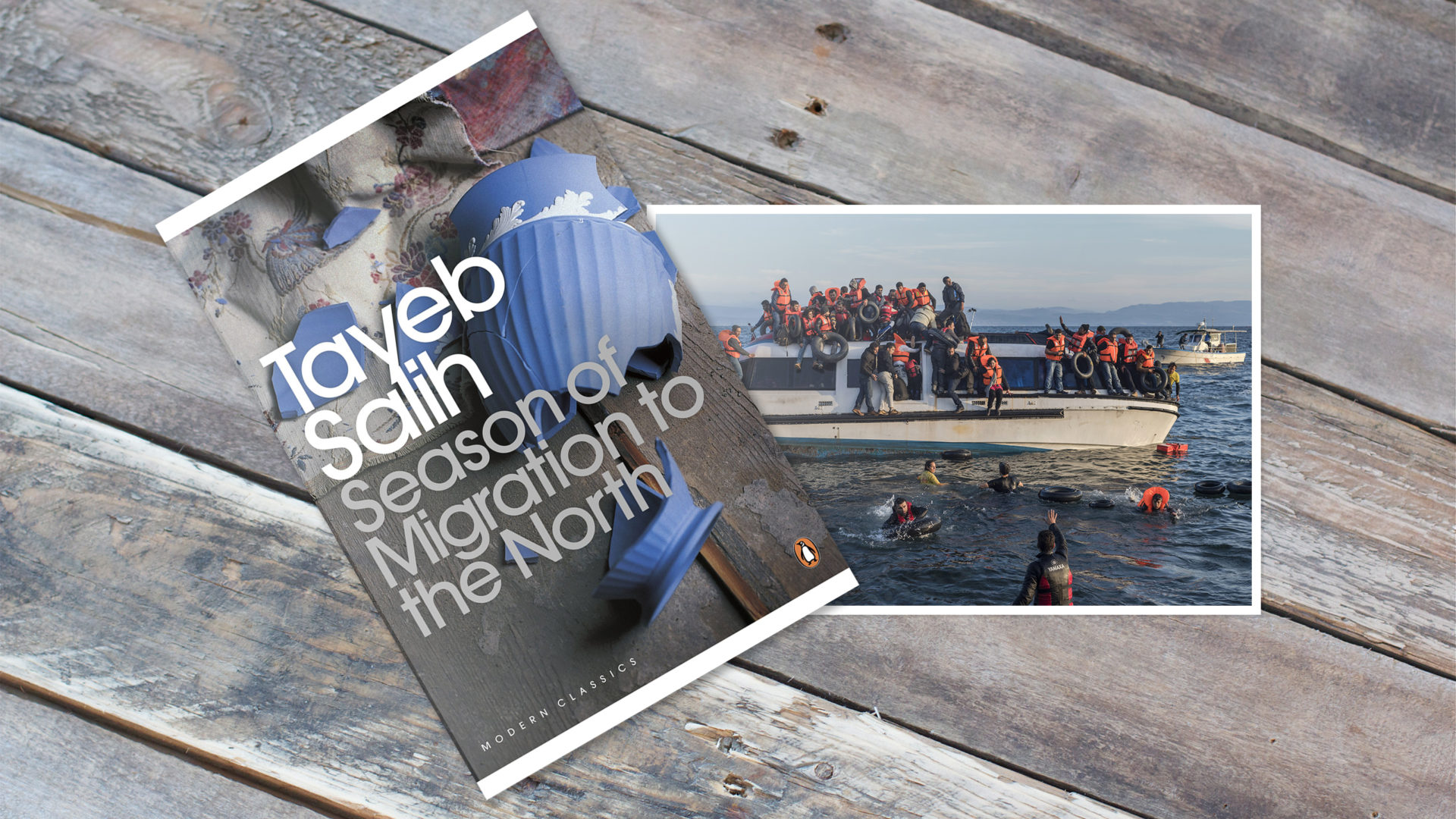

In the 1960s, long before Sudan was blacklisted as a hotbed of terrorism, the Sudanese novelist Tayeb Salih published a novel that is considered a masterpiece of modern Arab literature. Titled Season of Migration to the North, the novel traces the life of Mustafa Sa`eed, a precocious Sudanese boy who eventually gets to study in London but who, in an attempt to resist the West’s seductive hold on him, turns into what we may nowadays call a lone-wolf terrorist, striking back at the West by killing his English wife. Unsettled in England, Mustafa returns to his native country and starts a new life. But he fails to adjust. Torn between cultures and a misfit in both, he brings his tormented life to an end by throwing himself in the Nile River.

The case of Mustafa Sa`eed is one of the examples I used in my book, Unveiling Traditions: Postcolonial Islam in a Polycentric World, published by Duke University Press in 2000, and in my article “The Failure of Postcolonial Theory After 9/11,” published in the Chronicle of Higher Education, to show how the clash of Islamic and Western values affect Muslim minds and lead to the sorts of behaviors we are witnessing today among young displaced Muslims in Europe and, sometimes, America. It is, in fact, one of the major themes in 20th-century literature authored by Arab and African Muslims.

Novelists like the Senegalese Cheikh Hamidou Kane, the French-Moroccan Goncourt-prize winner Tahar ben Jelloun and others have done a good job of documenting the violence that flows out of a Muslim’s migration to Europe. The young, promising immigrant (often male) in their accounts ends up being torn between two commitments—one to the Islamic tradition he has left behind, and one to the secular future that promises a better education and a place in the modern world. Doubly alienated, few, if any, are able to navigate these conflicting paths and emerge unscathed from their traumatic experience.

Novels like Season of Migration to the North show that Muslim resentment and resistance are caused by the West’s forced intrusion into Muslim societies, but there is more to this clash of cultures than old-fashioned imperialism. People who have grown to believe that the values of Islam are the only ones acceptable to God could spend a lifetime wrestling with how to behave in the liberal (or libertine, as they see it) societies of Europe or America. Many live in self-imposed alienation, trying to replicate life in a Muslim city or village in their homes, while staying away from anything that would defile their faith.

As Muslim refugees continue to stream into the West (seeking the freedoms that repel many of them), we should expect such cultural traumas and start thinking of ways to diffuse their impact. States should pursue an aggressive policy of integration, making sure that Muslims get a good education and good jobs, if they deserve them. Denying Muslim job applicants an opportunity just because they have a Muslim name (as sometimes happens in Europe) is counterproductive, undemocratic, and unpatriotic.

Muslims, too, should be expected to think differently about their traditions and understand that just like Jews and Christians have had to adapt to modern ways, they must make an effort to rethink their convictions and be open to new ideas, however jarring to their faith they may be. Western culture is not the enemy of Islam but the latest stage of a global civilizational process that has been embraced by nations as far apart as China and Mexico—both home to great civilizations older than Islam.

This change, however, can’t be imposed from the outside or bombed into existence, but instigated from within, by allowing freethinkers to write freely and defending their rights aggressively if they get threatened. Western cultural institutions could help by translating and disseminating books, sponsoring lectures, and explaining how Europe’s faith-based societies turned into secular and democratic nations.

We all must be sensitive to other people’s faiths, but we should be very careful not to misdiagnose or downplay the challenges facing us as Islam becomes increasingly intertwined with Western and other world cultures. Whether they immigrate to Europe or stay home, Muslims experience their encounter with Western lifestyles as a form of alienation. If they are in the majority, they’ll try to banish them outright, as has happened in Iraq since the downfall of Saddam Hussein.

Another contributing factor to the Muslims’ sense of dislocation is their underdevelopment. They know they depend almost entirely on the Western goods and services to build their societies, yet they are made to believe that they are God’s chosen people. This can be frustrating to literalists and can lead young people to join extremist movements that promise strength through uncorrupted faith.

In the end, whether in the West or in their native lands, Muslims have not had the opportunity to work out their place in the modern world and become active contributors to it. This is why we should invest heavily in cultural projects to make sure they have the resources to make the transition. Just like literature warned us about what to expect long before we entered this turbulent era, Western-sponsored humanities programs and other cultural projects could help pave the way to a better future for all.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.