Philip Pilkington, the author of The Collapse of Global Liberalism And the Emergence of the Post-liberal World Order (Polity Press, 2025), has an urgent message for us: The West, which gave birth to the liberal project half a millennium ago, is coming undone due to the delusions late liberalism has generated in the last seven decades or so. As the political expression of the Enlightenment, liberalism set itself against “personal hierarchical relations,” including monarchies, in favor of “contractual relations.” Synonymous with modernity, liberalism, in its broader sense, encompasses communist and fascist movements, since both are reactions to severe social dysfunctions and are, therefore, “ghosts of liberalism’s own making.” Fascism, in this reading, is “a violent reassertion of hierarchy” against the unnatural order championed by liberalism.

Historically, there have been two types of liberalism: soft and hard. The first was limited in scope; the second is applied to all facets of social life. By the second half of the twentieth century, soft liberalism evolved into a hard variety, moving from a social democratic model to a neoliberal, or hyperliberal, one. For the sake of competition, manufacturing was outsourced to low-wage countries to generate better financial outcomes—“in the abstract,” Pinkington emphasizes. The United States and other nations have transitioned into service economies, fetishizing “brain work” associated with new technologies, although there is no valid evidence that such technologies increase productivity. If anything, the United States switched from being a beneficiary of trade surpluses to being hammered by ever-widening deficits during its neoliberal phase.

Compare this with the Chinese approach. In the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping charted a course for his nation that blended economic (soft?) liberalism with hierarchical social and political relations. The Chinese wanted nothing to do with “bourgeois liberalism.” They avoided a Western-style market economy in favor of state dirigisme in order to serve national interests better. Even though the Chinese borrowed from Marx, their leaders were ultimately inspired by their Confucian heritage. They had no qualms keeping an illiberal form of government, just as Russia has chosen to do after the dizzying period of the “gangster economy” that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union.

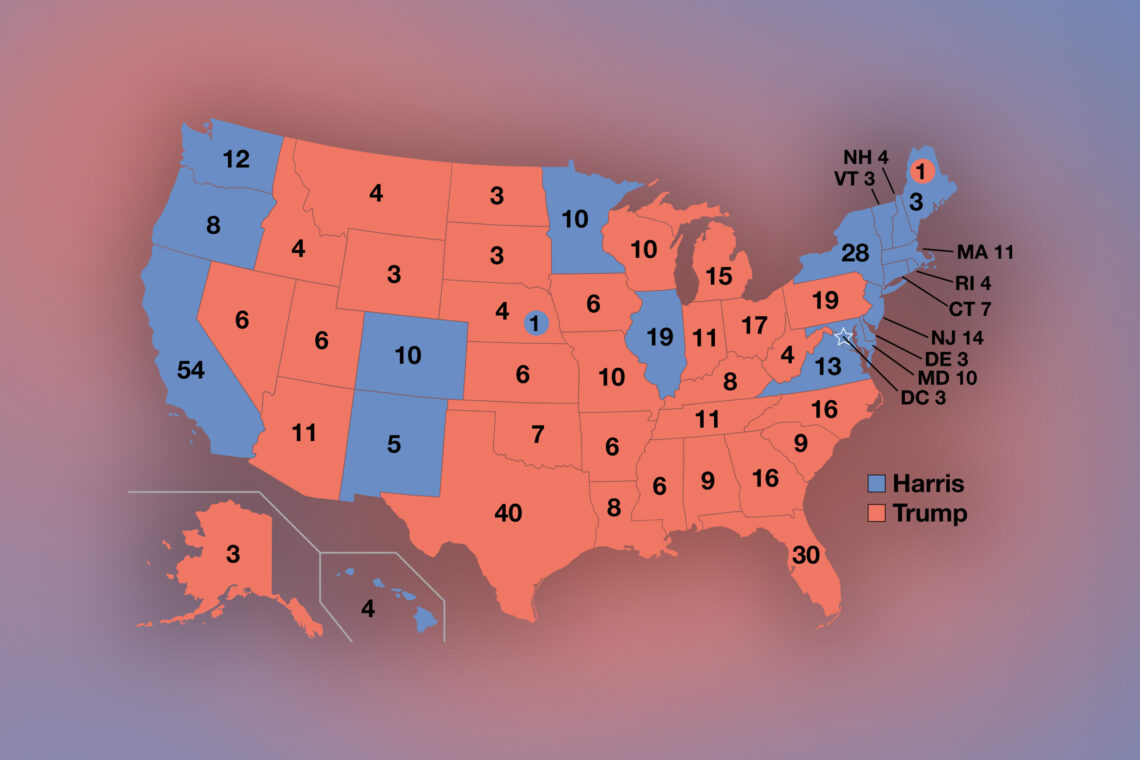

According to the author, the Russo-Ukrainian war is a major dividing line in history, especially since “the Western response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine was one of the largest geostrategic and economic blunders made by any country or group of countries in modern history.” While the United States imposed sanctions on Russia, China very diplomatically adopted what has been labelled “pro-Russia neutrality.” Trade between China and Russia increased by 47% between 2022 and 2023, helping Russia’s economy to grow despite sanctions. Still, by freezing Russia’s foreign exchange reserves, the West sent a warning to other nations to diversify their portfolios. (As I am writing this, India, hit by American tariffs, is also moving closer to China.)

The technology that the United States relies on to maintain its military dominance over its potential non-Western rivals is, paradoxically, turning into a wasteful expense. When military-sponsored inventions find commercial applications and become commodified, they get repurposed by adversaries to fight back and reduce America’s superiority on the battlefield. Thus, in absolute dollars, the US gargantuan military budget doesn’t translate into automatic advantage since other nations, including China and Russia, not to mention rogue entities like the Yemeni Houthis, can arm themselves with much smaller budgets due to what is called “purchasing power parity.” (What costs ten dollars in the United States may cost only five in other parts of the world.) Technological gadgetry may help liberals pursue wars without casualties—at least to themselves—but since high-tech weaponry doesn’t necessarily translate into positive outcomes, it remains a lucrative business for the military industrial complex. War, in this sense, is more about doing business than about achieving victories.

The West is not falling apart because of outside threats, but because “global liberalism is already dead” and we are living through its “postmortem cadaveric spasms.” Marriage and fertility rates are too low to ensure demographic and cultural survival. Dating apps—the matchmakers of the tech age—encourage contractual relationships, including “sexual encounters and short-term dating,” not marriage and family formation. Low fertility rates have a deleterious effect on the entire structure of the liberal social edifice, including pension and retirement schemes. As baby boomers and retirees command an increasing portion of the economic pie, abandoning younger generations to precarious lives, the young may have no option but to round up their elderly and confine them in death camps before they dispose of them altogether in “a sort of Holocaust.” Again, absent robust policies incentivizing family formation, importing immigrants won’t mitigate any host nation’s long-term demographic issues.

Liberalism has allowed the West to luxuriate in a life of material abundance while condemning its people to a Sisyphean struggle to make ends meet and almost everyone to an impoverished experience of their humanity. It has devastating effects on mental health treatment, reduces traditional diplomacy to advocacy for bizarre Woke agendas, channels the traditional need for religious experiences into more than a trillion-dollar “wellness industry,” offers virtue signaling opportunities to self-delusional consumers who think recycling will redeem their trespasses, and coerces non-Western nations into shaping their futures in the West’s ephemeral image.

It may be hard to imagine life without liberalism, but the latter, Pilkington concludes, “has collapsed the principles on which Western societies are founded and, unless something changes and these societies revert to their foundational morality, they will almost certainly slide into increasing levels of barbarism.” In other words, the situation is utterly hopeless unless the West reverses course and goes back to a medieval hierarchical model that reflects natural law. If I understand the author’s agenda for renewal, it includes the unlikely combination of a return to the solid classical Christian spirit with modern economic policies to balance global trade, including the implementation of John Maynard Keynes’ overlooked supranational currency known as bancor.

If such a magical combination strikes readers more as an expression of nostalgia for a lost or imagined past than a practical remedy for current global dysfunctions, it is because it’s hard to build a wholly formed society that is governed by a natural ethos. I agree that a global post-liberal regime needs to be “country- and region-specific” (my first academic book, Unveiling Traditions, published in 2000, was a call to a polycentric world), but to get there, the author needs to take a clearer stance on capitalism and its deleterious impact. Since Pilkington thinks that liberal capitalism is “becoming far too aggressive” to support natural hierarchical values, what is his alternative to this economic system that has spread its tentacles around the world? Isn’t capitalism, which prizes contractual relations, the economic foundation of liberal ideology? Could one dismantle liberalism without doing the same for capitalism? Pilkington shares Karl Marx’s description of capitalism as a dissolving agent, but he calls it liberalism, as if calling out capitalism for its boom-and-bust effects is too heretical an idea. One might describe capitalism as the new religion of globalism, with a hierarchy that consists of a few multi-billionaires lording it over masses too distracted by vacuous forms of entertainment and self-affirming technological devices to think of better prospects for our embattled humanity.

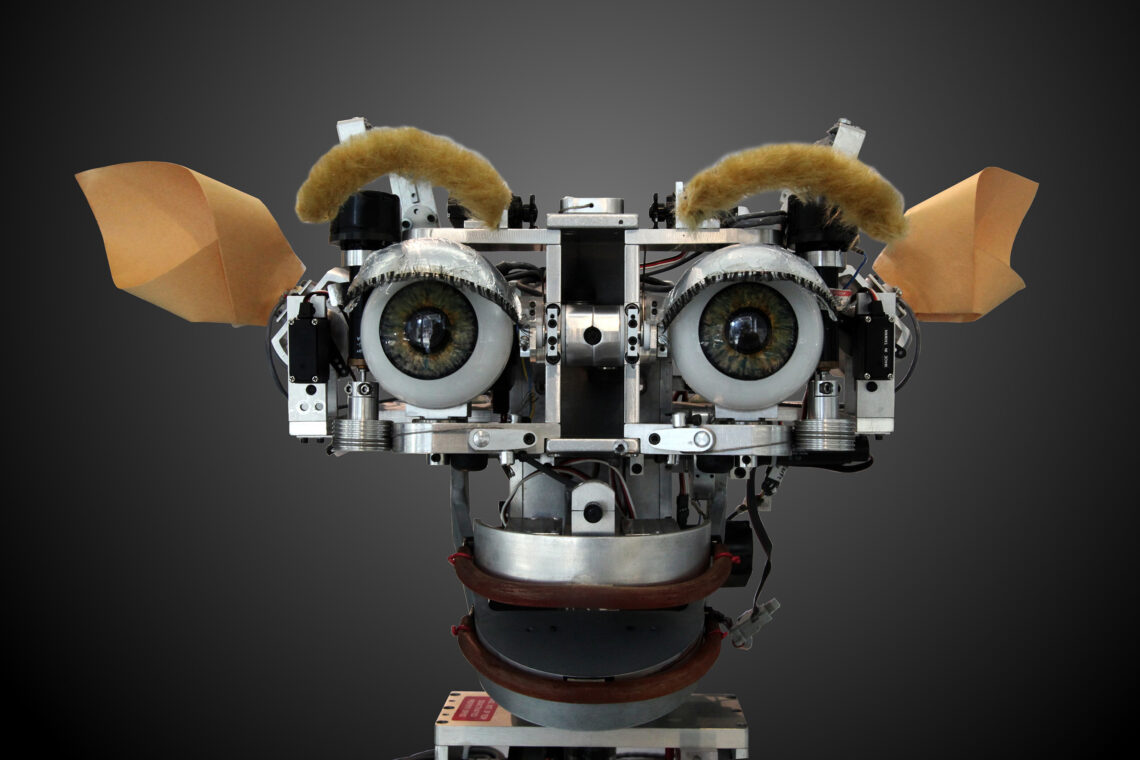

There is also the matter of artificial intelligence, which is in the process of removing us further from nature and creating a new race of angels to take over the world. Even in the best-case scenario for what many expect to be an apocalyptic time for humans, these new angels will do our jobs for us, reducing humans to idle hyperconsumers feasting on a cornucopia of products, thanks (if we are lucky) to a Universal Basic Income. As I am writing this, the conversation about our future is moving in this direction; no one at Silicon Valley (where tech moguls are fixated on space exploration and migration to Mars) is inventing a time machine to take us back to the twelfth century.

It so happened that when I was reading The Collapse of Global Liberalism, I finally caught up with the last season of the Netflix series about the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. In one episode of The Crown titled “Ruritan,” the queen, following the election of the wildly popular Tony Blair, wonders whether the monarchy is still popular. A focus group reveals that more than half of the country has negative views of the institution. With its anti-Catholic Protestant bias, it has become strangely anachronistic (and incomprehensible) in the modern world, employing people with such titles as Grand Falconer, the Queen’s Herb Strewer, Washer of the Sovereign’s Hands, the Queen’s Guide to the Sands, Yeoman of the Glass and China Pantry and the Lord High Admiral of the Wash. The Queen’s sister Anne argues that it is precisely this anachronistic world that people want in their monarchy; it allows them to transcend their mundane liberal lives. But is this monarchy the solution to the collapse of liberalism in Britain?

The past, with all its solid splendors, is not recoverable. How, then, do we build a post-liberal future? Unless we are overtaken by a new species of artificial creatures in the next decade or so, Pilkington’s Pandora’s box of questions could serve as the first step in a global attempt to save what’s left of human civilization.

Related articles by Anouar Majid:

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.