Over the last few decades, a consensus has been growing in major hubs of science and technology, especially in the United States, that the human race as we know it is on the verge of extinction and will be replaced by a new species of artificial creatures without a human body and its complex brain. This is not science fiction or conspiracy theory thinking. This is as real as it gets, and yet there is a general amnesia about this shocking fact because, I suspect, few people are equipped to grasp the technical details of artificial intelligence (AI) or other technologies that are ruling our lives. Fewer still can glimpse and truly understand the religious and philosophical foundations that are in the process of destroying humanity. We are dealing with a phenomenon with no historical precedent. Let me repeat this: We are confronting a situation that has never happened since the emergence of Home sapiens some 300,000 years ago. As the popular historian Yuvan Noah Hariri put it recently in an interview, “The most important thing to know about AI is that it is not a tool, like previous human inventions. It is an agent, in the sense that it can make decisions independent of us.” Nuclear bombs do not drop themselves on people without human agency, but AI makes its own decisions and acts without regard to our wishes.

Seeking to be at the vanguard of the future, nations and businesses are racing to invest heavily in AI, believing that such early actions would turn them into major players in the global economy. As in the ancient days of computers and the Internet, forward-looking educational institutions are dutifully integrating AI into their curricula to prepare their students (yet again) for a brave, new world. On the face of it, this is a laudable goal, but like the vast majority of intellectuals and scholars on our planet, including religious leaders, they simply have no idea about the hidden vision that led to the creation of Artificial Intelligence.

AI hasn’t been designed to preserve traditional human values, but to eradicate them and dispense with them altogether. We are, as Elon Musk told CEO Jack Ma of Alibaba in a 2019 debate, mere fodder for our successor species. “You could sort of think of humanity,” Musk said, “as a biological bootloader for digital superintelligence.” In this posthuman future,” wrote Joe Allen in his 2023 book Dark Aeon, “the bits and bytes of our personalities will be digitized and transferred to an e-ghost who goes on evolving in endless virtual space, even after our bodies die. In other words, to upgrade our limited humanity, as described by a cabal of geniuses whose hub is Silicon Valley or San Francisco, is to self-destruct in favor of a more evolved, God-like species.”

More than three decades earlier, Vernor Vinge, an American professor of mathematics and a science fiction writer who popularized the concept of “Singularity,” presented a paper at NASA predicting that “Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly thereafter, the human era will be ended.” This is the same view held by the maverick transhumanist Hugo de Garis, who argued that the rise of “artilects” or “artificial intellects,” will spell the end of humanity as we know it.

Western technologies of the last century, including nuclear power, space exploration, genetic engineering, the Internet, and artificial intelligence, to name only the most prominent examples, are not ideologically innocent enterprises seeking to improve the world’s cultures and traditions. Although the pioneers and leaders associated with these inventions may be secular and profess genuine humanitarian ideals, they are unconsciously writing the latest chapter in an aspect of Christian ideology that, for reasons still not fully understood, emerged in the Middle Ages. We assume that evidence-based scientific work clashes with the supernatural worldview of religions and that technology has a neutral impact on our cultures and traditions. But that is not the case at all. After the German Nazi Wernher von Braun, who headed “the world’s first precision-guided, long-range, rocket-powered missile,” was taken into custody at the end of World War II by the U.S. military, he was reborn as a Christian in Texas. His faith didn’t prevent him from developing ballistic missiles for his new country. The whole thing was part of a divine plan. “’It has frequently been stated that scientific enlightenment and religious beliefs are incompatible,” he said in a commencement speech in 1958; “I consider it one of the greatest tragedies of our times that this equally stupid and dangerous error is so widely believed.’” Engineering nuclear armageddon will only precipitate the longed-for apocalypse anyway. Today’s doomsday technology that is on the verge of destroying our cultures and religions is powered by a forgotten aspect of Christian theology that had been declared a heresy by the Catholic Church at the Council of Ephesus in 431.

As the twentieth century was coming to a close, the freethinking Jewish scholar David F. Noble, who studied under the inimitable sociologist Christopher Lasch, published a masterpiece of historical research that unveils the prevailing illusion that we have bypassed the Christian faith and now live in a purely secular world. In The Religion of Technology, Noble casts his eye on many centuries of European history to argue that modern technology is rooted in Christian beliefs that are more than seven hundred years old and that, by implication, without this enduring Christian worldview, our technologies would not have taken the course they have.

At some point in the early Middle Ages, a shift of religious outlook occurred within the Christian community when the practical labor (hitherto associated with slaves and women) that had been disdained by Christian elites like St. Augustine as a distraction from spiritual devotion and the quest for grace was recast by Benedictine monks as indispensable for the Christian faith since productive work helps elevate man and restore his God-likeness that was lost after the Fall. By the ninth century, the Carolingian philosopher Erigena included medicine and architecture in the seven artes mechanicae (mechanical arts) of his age, arguing against the Augustinian view that such arts allowed for a redemption of man and his restoration to his prelapsarian state. In the twelfth century, the Augustinian canon High of St. Victor, arguing against St. Augustine’s spiritual perfectionism, believed that repairing man’s physical life was equally indispensable. The Franciscan friar Bonaventure agreed that pursuing the mechanical arts was a virtuous endeavor.

Such a novel attitude coincided with the emergence of millenarianism based on the prophecy in the Book of Revelation that the Messiah will return to lead a transformed world for a thousand years before the final apocalypse. (This theology has other eschatological variations, but that is not important for our purposes here.) For the Franciscans, the advancement of the useful arts was part of their “millenarian anticipation,” as was the case with the Franciscan English polymath Roger Bacon, whose vision anticipated the invention of “self-powered cars, boats, submarines, and airplanes.” Because “a worldwide conversion to the Christian faith was a necessary precondition for, and unmistakable indication of, the coming of the millennium,” even the explorer Christopher Columbus believed that his ultimate mission was the conversion of Muslims and all idolators to the Catholic faith.

In the following centuries, preceding the Reformation, the alchemists and illuminati were motivated by the same will to correct Adam’s mistake. “Because of the darkness caused by Adam’s sin,” wrote the German polymath Cornelius Agrippa, “the human mind cannot know the true nature of God by reason, but only by esoteric revelation.” He argued that “it was precisely this power over nature which Adam had lost by original sin, but which the purified soul, the magus, now could regain.” He argued that “an illuminated soul” would allow us to return “to something like the condition before the Fall of Adam, when the seal of God was upon it and all creatures feared and revered man.”

Paracelsus, the founder of pharmacology, and Albrecht Dürer, the celebrated German artist, were inspired by the same religious urge. The Dominican friar Tommaso Campanella’s utopian City of the Sun was based on an educational system combining “training in the mechanical arts with that of the liberal arts” to allow people “the wisdom needed to understand, and to live in harmony with, God’s creation.” The German theologian Johann Andreae prescribed a similar curriculum to the four hundred inhabitants in his utopian Christianopolis,. In Fama Fraternitatis, one of two manifestos of the mysterious and esoteric Rosicrucians, the latter assume that God expects men to raise their worth and “return to the Paradise which Adam lost” by perfecting the arts.

Like Spain in the fifteenth century, England’s conquest of America in the seventeenth was motivated by a similar millenarian spirit. Following the Protestant Reformation, a literal reading of the Bible, especially the Old Testament, intensified the “preoccupation with salvation” (soteriology) and “speculation about the end-times” (eschatology). Adam’s disgrace occupied a central role in this doctrine. Because he forfeited “total dominion” through the Fall, the focus was on how the useful arts could help reverse the decline and exile suffered by humans since then. “The technological discoveries of the Renaissance, particularly those relating to gunpowder, printing and navigation,” wrote the British historian Charles Webster, “appeared to represent a movement towards the return of man’s dominion over nature . . . . The Puritans genuinely thought that each step in the conquest of nature represented a move towards the millennial condition.” The poet John Milton was adamant that nature “would surrender to man as its appointed governor, and his rule would extend from command of the earth and seas to dominion over the stars.” To the English philosopher Francis Bacon, the ultimate aim of science is “the relief of man’s estate” through the useful arts. The biographer Paolo Rossi described Bacon’s ultimate goal as nothing less than the restoration of man’s prelapsarian power to have control over all things. As Milton put it, the end of education “is to repair the ruines [sic] of our first parents by regaining to know God aright, and out of that knowledge to love him, to imitate him, to be like him.”

Not only did Robert Boyle, the founder of the Royal Society of London, call for the renewal of Adamic knowledge, but he also thought that the new “scientific virtuosi” of his age could supersede Adam himself and assist God in finishing the project of creation. “Despite their caveats about the necessity of humility,” Noble comments, “and despite their devout acknowledgment of divine purpose in their work, the scientists subtly but steadily began to assume the mantle of creator in their own right, as gods themselves.” It is, therefore, not surprising that Francis Bacon would imagine men creating a new species and becoming gods in his utopian novel New Atlantis. Empowered by the compounding effects of science and technology, scientists were slowly moving away from the medieval quest for immanence to one of transcendence. Instead of seeking a restoration to Adam’s condition before his fall, they now aspired to do better than him and be co-creators with God.

Choosing the engineer as their new protagonist and spiritual hero in the millenarian cosmic drama, the Freemasons, probably influenced by the Rosicrucians, opened their Constitutions of the 1720s with this sentence: “Adam, our first parent, created after the Image of God, the Great Architect of the Universe, must have had the Liberal Sciences, particularly Geometry, written on his Heart; for ever since the Fall we find the principles of it in the Hearts of his offspring . . . . ” The Freemasons pioneered the field of civil engineering (“to distinguish it from a military function”), founded the first professional engineering school, the École des Ponts et Chaussées, as well as the École Polytechnique in Paris, which became the world’s premier engineering school.” The great French sociologist Auguste Comte, founder of the “Religion of Humanity” based on his philosophy of positivism, was “a polytechnician through and through.” His type of secular-sounding millenarianism was shared by socialists.

The English discovery of America was akin to a return to Eden, and Americans, in a sense, were new Adams. The poet Walt Whitman saw himself as the “chanter of Adamic songs, through the new garden the West.” The civil engineer John Adolphus Etzler was dedicated to re-establishing “the Paradise that Adam lost for mankind.” The Harvard professor Jacob Bigelow, who coined the term “technology,” announced that “we have acquired a dominion over the physical and moral world, which nothing but the aid of philosophy could have enabled us to establish.”

Closer to our era, the scientist Leo Szilard who played a major role in developing a nuclear chain reaction and the first atomic bomb in 1945 recommended the field of “nuclear physics” because “only through the liberation of atomic energy could we obtain the means which would enable man not only to leave the earth but to leave the solar system.” Edward Teller, who worked on the H-bomb project, displayed a “religious dedication to thermonuclear weapons.” While the possibility of Armageddon delighted the evangelical preacher Jerry Falwell who asked his followers to anticipate “a nuclear holocaust” that would allow “God to dispose of this Cosmos,” other scientists in the nuclear family, echoed Szilard’s dream (inspired by H. G. Wells’ novel The World Set Free), and fantasized about escaping this impending holocaust by leaving the planet in a starship. Rod Hyde, inventor of nuclear-weapons technology and designer of his own “nuclear-bomb-propelled starship,” couldn’t have been clearer: “What I want more than anything is essentially to get the human race into space. It’s the future. If you stay down here, some disaster is going to strike, and, you’re going to be wiped. If you get into space and spread out there’s just no chance of the human race disappearing.”

Exploring space and escaping from a fallen world is also a centuries-old European idea. During the seventeenth century, the millenarian mystic Tommaso Campanella wrote to Galileo explaining how he had “read new meaning into a familiar verse, ‘and I saw a new Heaven and a new earth’—namely, that the moon and the planets were inhabited.” Johannes Kepler wrote a friend asking: “Would it not be excellent to describe the cyclopic mores of our time in vivid colors, but in doing so—to be on the safe side—to leave this earth and go to the moon?” He even dreamt of being catapulted into space as if shot from a cannon. The English philosopher and bishop John Wilkins later commented that “so soon as the art of flying is found out, some of their Nation will make one of the first colonies that shall inhabit that other world.” By the nineteenth century, these speculations turned into solid prophecy in the writings of the French Jules Verne, who was inspired by Kepler.

In his 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon, Verne predicted the entire cycle of launching a capsule into space and splashing it back at sea. Perhaps this would be the way to create The Eternal Adam, as he titled his last work. “Project Adam” would also have been the name of the U.S. Army Ballistic Missile Agency to launch a man into space in 1959. When the first manned flight to the moon took place in 1968, the first thing the astronauts broadcast back to the world was the first ten lines in the Book of Genesis. And when Apollo 11 returned from the moon following its lunar landing, President Richard Nixon announced that “This is the greatest week since the beginning of the world, the Creation.” It is for this reason that the American historian Walter McDougall wrote that “we have never, from Protagoras to Francis Bacon to Tsiolkovsky, been able to separate our thinking about technology from teleology or eschatology.”

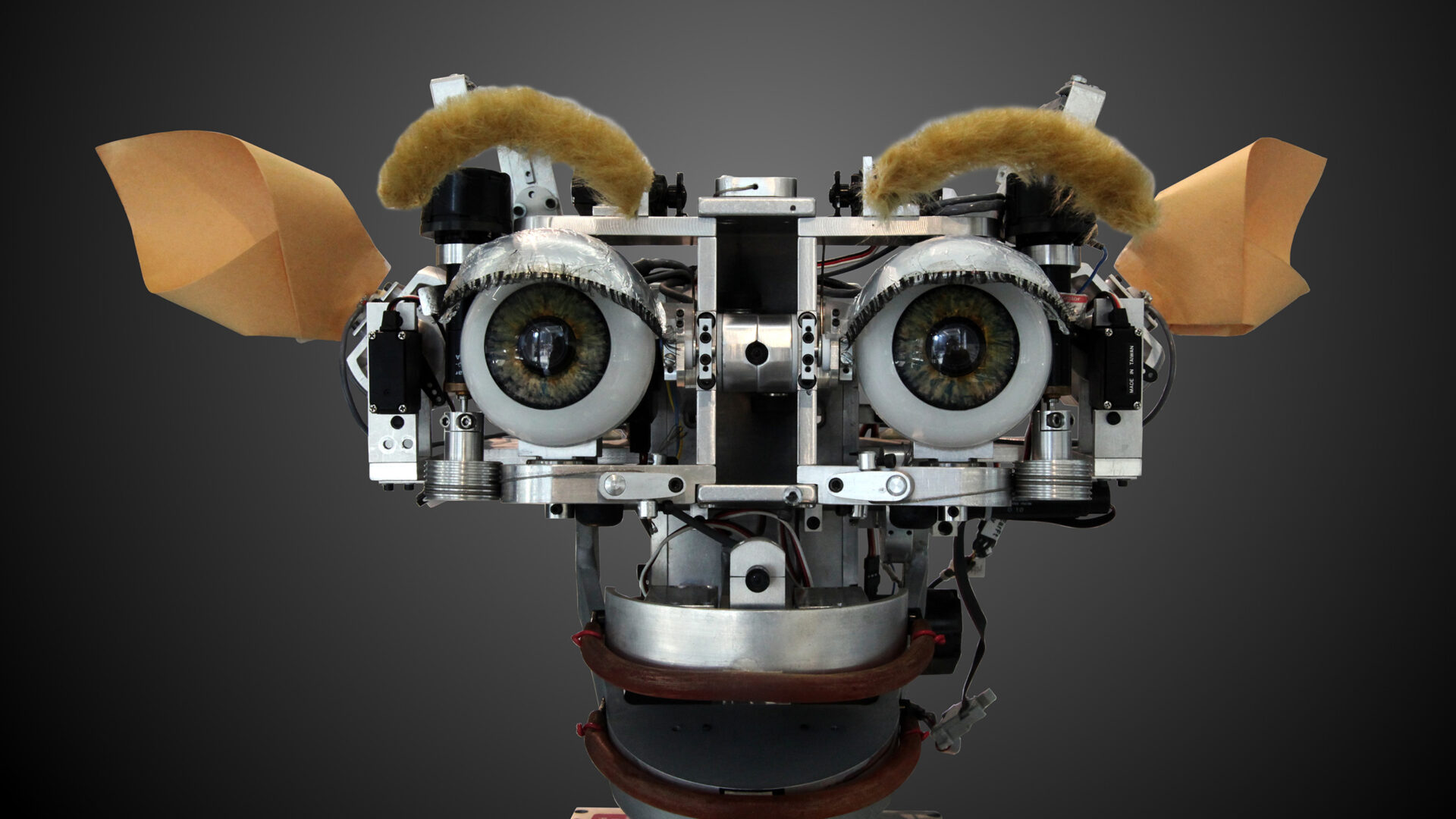

Finding refuge in space and populating another planet do not, in the end, change human nature, which is painfully entrapped in a very mortal body. Many in the techno-utopian world believe that the body is a hindrance to pure thought, which is the divine and immortal aspect of humans. When René Descartes imagined “thinking without the body,” he, in a way, validated the quest for a pure thinking machine that would dispense with the body altogether and be rejoined to God in a pure state. The troubled genius English mathematician Alan Turing, who was behind the creation of electronic computers and artificial intelligence, stated that “we may hope that machines will eventually compete with men in all purely intellectual fields.” More than that, he envisaged a time when such machines would not only transcend the body but also human intelligence itself.

Like space exploration, artificial intelligence was officially launched as a military project in 1956, at the height of the Cold War. Mark Minsky, a leading member who directed the AI project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was clear about the indisputable value of machines over flesh-and-blood humans, whose bodies are nothing more than a “bloody mess of organic matter” and their brains a mere “meat machine.” Notions of “cyborgs” and “cyberspace” were coined to describe this emerging reality. Cyberspace became Paradise Found, “a place where we might re-enter God’s graces . . . laid out like a beautiful equation,” wrote the president of a software company in Texas.

To attain a “postbiological” state of pure thinking, it behooves the mind to free itself from the brain. Mortal Homo sapiens would thus be replaced with immortal Machina sapiens. The demise of flesh-and-blood human beings and their replacement with artificial intelligence would simply be the next phase in the long story of evolution. Just like a brain needs a body to sustain it, so does artificial intelligence need silicon-based artificial life to keep it functioning. By so doing, biology-bound humans will produce a post-human species. “With the advent of artificial life,” said J. Doyne Farmer, one of the leading advocates of artificial life in the 1980s, “we may be the first species to create its own successors.”

As space exploration and artificial intelligence were being developed, the human body was being subjected to a decoding that would unveil its own structure. One could argue that the process began in the 19th century when the Moravian Augustinian priest pioneered the field that became known as genetics. When the American molecular biologist James Watson and his English colleague Francis Crick deciphered the double-helix structure of DNA, Crick announced that they had discovered the secret of life itself. “This is for me,” said the Spanish eccentric painter Salvador Dalí, “the real proof of the existence of God.” By the 1980s, Robert Sinsheimer, president of the University of California at Santa Cruz, was one of the strong voices pushing the U.S. government to fund the mapping and sequencing the entire “human genome,” a project that was once directed by the born-again Christian Francis Collins, who, from 2009 to 2021, served ss the director of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The Human Genome Project, “one of the greatest scientific feats in history,” as its website declares, was completed to great fanfare in 2003.

In the 1920s, the Irish life scientist and X-ray crystallographer J. D. Bernal could matter-of-factly declare that “normal man is at an evolutionary dead end.” In his view, a time might come when “consciousness itself may end or vanish in a humanity that has become completely etherealized, losing the close-knit organism, becoming masses of atoms in space communicating by radiation, and ultimately perhaps resolving itself into light.” As the American geneticist Elving Anderson would put it decades later, “the earth does not need more humans.” Long before Elon Musk brought the world’s attention to the possibility, Anderson was already dreaming of colonizing Mars.

As these doomsday technologies are being invented and perfected, their promoters keep resorting to public relations and marketing strategies, trying to convince the world’s captive populations that such technologies, if used wisely, are designed to enhance the quality of human life. Instead of understanding the ideological origins of these technologies and their long-term ramifications, educated people around the world, including academics and political leaders, have become part of a global chorus mindlessly rehearsing the catchphrase that AI will enhance productivity and efficiency. The downside of AI is the elimination of many tedious professions when superintelligent machines start doing the work for us, and the upside is the opening up of new possibilities for leisure, thinking, and the enjoyment of a cornucopia of riches that technology will make available. (Faith in this future is so strong that Nvidia, the leading manufacturer of AI chips, recently added three trillion dollars to its worth, which now makes it a $4 trillion public company.)

One of the ambiguously reassuring apostles of AI is the former director of Google, Eric Schmidt, who, along with Craig Mundie of Microsoft and the late Henry Kissinger, published a book last year, not unsurprisingly titled Genesis, to discuss the pros and cons of artificial intelligence. Despite the soothing tone of the volume and the authors’ resort to examples from history, there is no doubt that if humans don’t cooperate with the machine and evolve into Homo technicus, they will be outpaced and left behind. Should rivalries emerge among nations, which is to be anticipated, then only entities with the most powerful AI systems will prevail in kinetic wars that generally spare humans and destroy machines. Surrender, the authors of Genesis tell us, “will come not when the opponent’s numbers are diminished and its armory empty but when the survivors’ shield of silicon is rendered incapable of saving its technological assets, and finally its human deputies. War could evolve into a game of purely mechanical fatalities. . . .” Today’s superpowers like the United States and China would probably be safe in this new world order, but Muslims and Africans will have no power to resist a digital carpet bombing.

At this point, the Christian millenarian goals that propelled the centuries-long European quest for mechanical perfection have become all but forgotten, despite the recurring references to the Bible in books and papers. But Noble’s thesis, based as it is on a study of the European social imaginary, is the only one that should make sense, at least to members of the Abrahamic community. To my knowledge, almost no one seems to be aware that such technologies were designed to destroy the descendants of Adam and replace them with a new dynasty of immortal creatures whose power surpasses that of Adam and God combined. It’s not far-fetched to imagine an all-powerful algorithm dethroning old gods and turning into the Almighty deity of the future. Harari warned against this potential “digital dictatorship,” but he also consecrated Silicon Valley, the epicenter of most of these anti-human technologies, as the “New Jerusalem.” In line with this remapping of sacred geography, he told the World Economic Forum in 2020 that “The twin revolutions of infotech and biotech are now giving politicians and business people the means to create heaven or hell.” Without the hubris of those seeking to supersede the biblical god, Harari limits his prediction to the mere restoration of Adam to his prelapsarian status: “When biotechnology, nanotechnology and the other fruits of science ripen, Homo sapiens will attain divine powers and come full circle back to the biblical Tree of Knowledge.”

The quest for Adamic restoration, bliss, and power was never meant to be for all people, only the elites dedicated to spiritual salvation. Modern-day successors to Benedictine, Franciscan, and other millenarian monastic medieval orders are pursuing transcendence not necessarily for the glory of God, but to be God-like, and they are funded and supported by military organizations and powerful businesses to do so. This is a dangerous turn in the millenarian playbook and was predicted by a 19th-century apostle of technological utopia. In his novel Looking Backward (1888), Edward Bellamy imagines an American utopia in the year 2000, an age that “may be regarded as a species of second birth of the race.” Bellamy’s enthusiasm for the magical powers of technology, however, was not to last. He eventually came to realize that such technologies were a threat to humanity. “This craze for more and more and ever greater and wider inventions for economic purposes, coupled with apparent complete indifference as to whether mankind derived any ultimate benefit from them or not,” he wrote toward the end of his life, “can only be understood by regarding it as one of those strange epidemics of insane excitement which have been known to affect whole populations at certain periods, especially of the Middle Ages. Rational explanation it has none.”

In The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve, the literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt shows that Adam was not taken literally or seriously by Jews and early Christians until St.Augustine, who identified sex as the “original sin” that led to our downfall. It is only through surrender to Jesus that we can be absolved from the tyranny of animalistic drives and reclaim our loftier place in God’s creation. One can, therefore, understand why the millenarian project based on developing the mechanical and useful arts to restore Adam to his prelapsarian abode was considered a heresy. We don’t hear the Pope or other Christian leaders warning their flock about the perils of AI because, I suppose, they can’t see the connection between today’s technology and the millenarian fervor of the Middle Ages.

It’s the same with Muslims. While some Gulf states are rushing to become hubs for AI servers, no one seems to be remotely aware that such technology is an affront to their faith. The Christian millenarian project of restoring Adam to his pure state through the development of technology, or the recent arrogant conviction that artificial life and genetic engineering would create a new immortal species from the vast wasteland of the Internet and make humanity redundant, is a grave form of disbelief. Nothing prevented God from keeping Adam in his Edenic environment or creating an immortal species, but, according to the Quran, He molded the first human from clay or black mud and asked his devoted angels (fashioned from light, according to Muslim tradition) to prostrate to him. The angels thought it was a bad decision and protested. God insists, however, and tells them that His will be done. And when Adam and his mate Eve violate their promise to God not to approach a forbidden tree, their naked bodies are exposed and, after God forgives them, they are expelled from their perfect dwelling and sent into their flawed human nature to earth. ‘Therein you shall live, and therein you shall die, and from there you shall be brought forth,” God tells the forlorn couple. The ultimate goal of a Muslim, then, is to seek mercy through prayer and devotion with the hope of recovering the paradisical world Adam lost. This is the human condition as God intends it. God chose His mud-made creatures as His viceregents, not his obedient, flawless angels made of light. The “artilects” that the apostles of artificial intelligence want to replace biological creatures, displace Adam, and become gods in their own right are, in fact, like the fallen angel Satan, who refused to prostrate to Adam and who is bent on misleading humanity. It is Adam’s act of disobedience, or his “original sin,” in the world of St. Augustine, that makes us human, and it is our imperfect nature, with its concomitant hope for redemption, that gives meaning to our lives. God had no intention of populating his creation with immortal ethereal creatures.

In 2023, a group of Heredi rabbis in New York, quoting the Bible and previous rabbinic rulings, published a proclamation condemning artificial intelligence because it “enables abomination, heresy and treachery without limits.” The reasons they give for such a prohibition don’t seem to include the fall of Adam, the arrogant attempt to restore him to his lost paradise through the development of mechanical and useful arts, or even to join God in the act of creation. Theirs seems to be a lonely voice fighting what seems a fait accompli. One doesn’t have to be religious to grasp the fear of the rabbis. Marxists and all sorts of progressives (who have been eerily silent on the matter) need to make their own proclamations. All of humanity is at stake.

Updates

(Since this topic is developing at a rapid pace, Anouar will be updating his article with new information as it becomes available.)

On August 12, 2025, the Wall Street Journal reported that scientists and technologists in Silicon Valley are investing huge sums of money to engineer babies with high IQs to withstand the power of AI creatures.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.