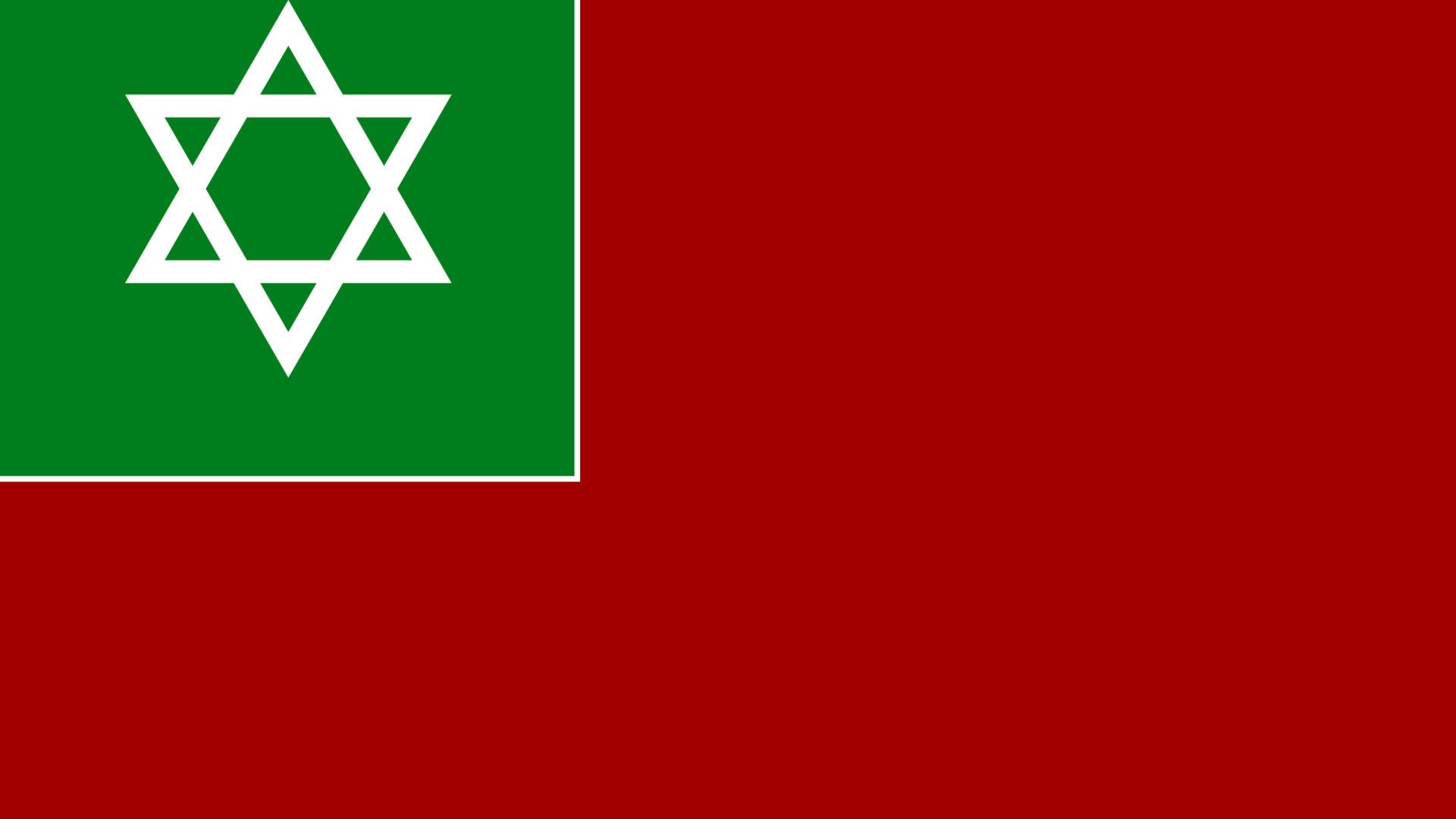

Not long ago, I came across a thought-provoking article by Jamal Boudouma about the history of Morocco’s flag and our national hymn. If you go back to Issue No. 262 of the Moroccan weekly TelQuel, you will find out that it was General Lyautey who, through a dahir (royal decree) promulgated on November 17, 1917, gave the Moroccan flag the shape and colors with which we are now familiar. TelQuel doesn’t mention that the French added a mini tricolore on the upper left corner to indicate who were the actual rulers of the country at the time, but this detail is not the point of the article. The point is to show that prior to this period, the Moroccan flag sported not the five-pointed star (pentagram), but the Star of David (the hexagram known in Arabic as Khatam Suleyman and in Judaism as the Seal of Solomon). Morocco’s Semitic heritage, which it shares with Jews, was acknowledged on the most visible symbol of the nation, until French colonialists thought differently. TelQuel goes on to record the history of our national hymn, first composed by one Captain Léo Morgan and only put to words in 1969, after Morocco’s national team had qualified to play in the soccer world cup of 1970. After a national contest, Moulay Ali Skalli’s “manbita al ahrar” (which, roughly translated, means “land of the free”) was selected by King Hassan II, who added a few touches to the lyrics.

Intrigued by this remarkably little known history of our national emblems, I consulted a major study of the flags of Islam and discovered that according to an old Spanish manuscript, a flag used in Morocco between the 11th and 13th centuries consisted of a white and black chessboard inside an all-red flag. It was an interesting compromise, indicating the various poles of commitment within the Andalusian-Moroccan sphere, with white referring to the Umayyads, black to the Abbasids, and red to the Fatimids, a Shiite group. By the 18th century, according to the political scientist and vexillologist Pierre C. Lux-Wurm, the black element had disappeared. (Vexillology, from the Latin vexillum, which, in Roman times, designated the standard of the army, is the study of flags.) The flag on a shipwrecked Moroccan ship displayed a red flag with two crossed white swords. By the 20th century, the Moroccan flag appeared with two gold-rimmed interlaced squares. Meanwhile, Abdelkrim Khattabi used a red flag with the white upper left part containing a crescent, while the red flag of the ephemeral Republic of Rif featured a white lozenge containing a crescent and the Star of David. The Star of David, in fact, was used in the Spanish zone of influence until 1956.

Reading more on the Seal of Solomon, or, as it later became known among the Ashkenazi Jews, the Star of David, one finds mutual influences in usage of this symbol among Jews and Muslims, as both sought to associate themselves with the legacy of the wise king Solomon (Shlomo, in Hebrew, which, as in Arabic, is associated with the term shalom, or peace), son of the other biblical figure, King David. Interestingly, it was the Alawite monarch, Moulay Suleyman (popularly known as Moulay Slimane in Morocco) who used the Seal of Solomon on the newly minted bronze coins in the late 18th century to add to the standard coin metals in the Islamic world—gold and silver—and, at the same time, protect the new money with the magical powers of his ancient namesake.

TelQuel’s article elicited surprise in Moroccan websites, such as Casafree and others, but scholars have long known that identities are often more imagined than not. Not a bad thing to keep in mind as many nations around the world are ready to annihilate their neighbors in the name of an elusive principle. The only protection we have against such tragedies is to remember that concrete humans are far more real than the ideologies that lead us to love or hate them.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.