After more than 17 years of residing in the United States, I finally made it to Washington D.C. to attend a convention in the last days of 2000. Like everyone else, I had read about the politics of the capital and the public’s low view of the insiders who inhabit that city; and in academia, I had read and heard about how the city was designed to enshrine the triumph of Western civilization over indigenous cultures. The sturdy marble columns, the cupolas, even the seasonal National Christmas tree and the Menorah facing the White House on the Ellipse were clear reminders that Washington is the transatlantic embodiment of Old World ideals—Mediterranean and biblical. If one were to stand away from Washington and survey the city this impression becomes unavoidable. But, as it turned out, my three-hour tour of the city a few weeks before the first millennial presidential inauguration gradually convinced me that the city was neither hopelessly corrupt nor clearly European.

Around 1 p.m. on a piercingly cold day, I boarded a small bus whose dexterous and entertaining driver (who also doubled as the tour guide) quickly picked up tourists from other hotels before starting us on our journey. Our group consisted of Spanish-speaking people, Israelis, Americans, an Italian couple, and myself. Fittingly enough, the first major monument we saw before we drove up Capitol Hill was the statue of Christopher Columbus and the three ships of his first voyage (the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria) dramatically set against the architecturally imposing Union Station. From the Hill, we were able to see the scaffolding for the inauguration and survey the vast Federal Mall. As we drove down Pennsylvania Avenue, we were shown the theatre where Abraham Lincoln was assassinated and stopped for a few minutes to walk around the Ellipse facing the White House. We then visited the Jefferson Memorial (a paean to Enlightenment thought) and the recently built FDR Memorial.

This stop was quite moving. I detached myself from my group to follow a limping Park Ranger who was solemnly leading a few people through the various chambers of that open-air monument built with massive granite rock. The Ranger dutifully paused in front of every major statement engraved on the rock to describe a phase in FDR’s eventful life. He spoke economically, almost as if he were struggling to keep an overwhelming sadness at bay. Like eager seekers, we retraced the life of a saint whose life culminated in the miracle of a fourth presidential election, followed by sudden death. The Ranger paused in front of the sculpture depicting FDR’s funeral cortege and said not a word. His last comment was about Eleanor Roosevelt and her humanitarian work. The Ranger then pointed toward what lay beyond the Memorial, as if the Mall and the city itself–clear testimonials to the revolutionary ideal of liberty–were ultimately FDR’s legacy. Didn’t FDR save freedom and democracy from the twin evils of poverty and fascism? A sense of mourning continued to pervade the Ranger’s presentation, while tourists, confused, moved about awkwardly. About ten minutes later, I found our guide at the entrance to the monument, ready to escort yet another group of unsuspecting pilgrims.

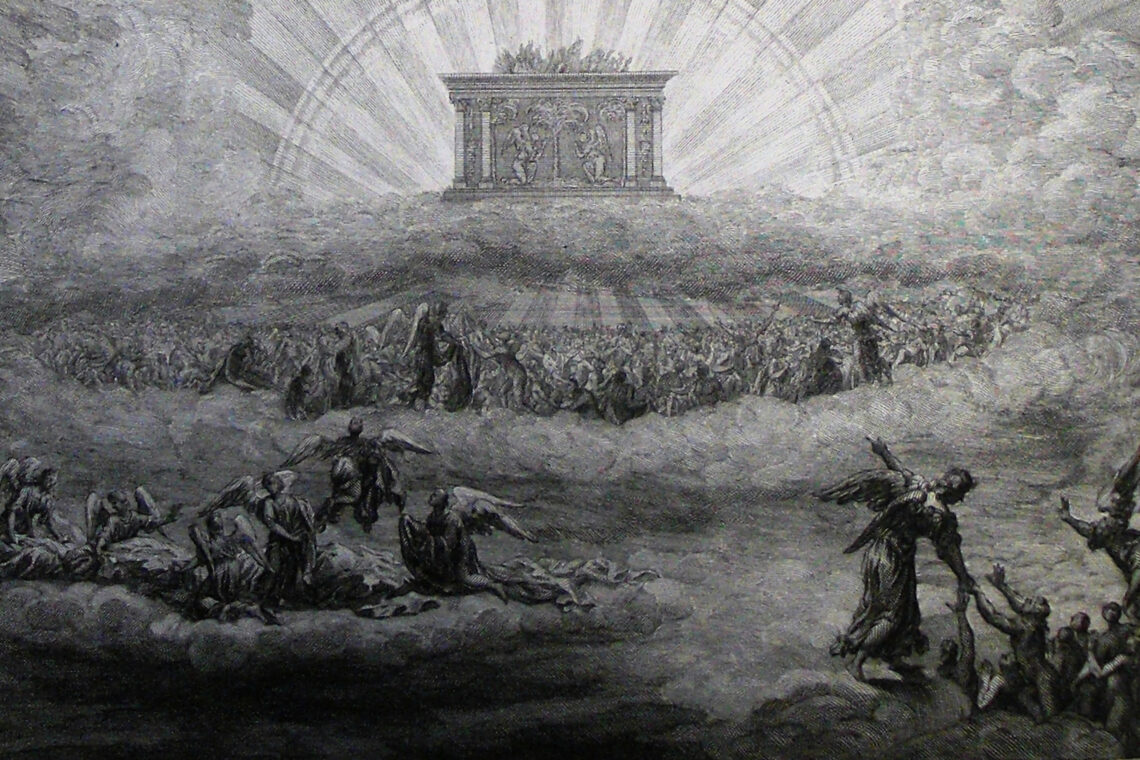

It was at this point that I was able to articulate a feeling that had seized me earlier in the tour. I realized that the only other time I felt like this is when I was visiting the ancient city of Teotihuacan in Mexico (whose impressive pyramids rival those of Egypt and whose ruins led the later Aztecs to name it “City of the Gods”), Palenque in Chiapas, Monte Alban in Oaxaca and other similar ceremonial Native American cities. Washington D.C. felt like an inextricable part of a continuum in this quintessential American legacy, a sacred temple run by a priesthood devoted to preserving the nation’s cherished myth of liberty. A strong spirituality and solemnity emanated from every engraving, every story, and every edifice. Rather inexplicably, the European architecture and biblical motifs somehow conspired to enhance this indigenous spirit, not eclipse it.

The visitor also comes to realize that Washington cannot easily be corrupted, despite all the proverbial criticisms of the city’s political culture and the regular failings of the establishment. The culture of consumerism, the city’s daily politics and not-so-democratic lobbying were totally erased by this vast shrine to the ideals of the Republic. The Arlington National Cemetery, the Iwo Jima, Vietnam, Nurses, and Korean War Memorials are grim reminders that country’s ideals are ultimately more enduring than the sum of the city’s political follies. Of course, I imagined America’s immortalized heroes (such as Jefferson, Lincoln, and FDR) to be saddened by history’s inexorable tendency to repeat itself. For wars happened after they tried to stop them and more American lives were lost in futile wars. But Washington D.C.’s monuments speak loud and clear against injustice, oppression, and war; and these solidly engraved ideals will ensure that the nation’s capital will remain the ultimate destination for American pilgrims seeking self-discovery and renewal. Such monuments will surely outlast the messiness of everyday life and remind people–American and foreigners alike–that a mighty American nation, founded on revolutionary and honorable ideals, has striven to elevate common human life to a level of dignity hitherto unimagined. The ideal has never been perfected, of course, and much remains to be done to enfranchise millions of citizens; but freedom is always a work in progress, and there is no reason to despair.

In a strange sort of way, I felt that downtown Washington D.C. was the least American of the cities I had so far visited. The dizzying lights and cacophonous noises of shopping malls and marketplaces were magically dimmed by the city’s monumental architecture and timeless truths about human dignity etched on almost every structure. And the Founding Fathers’ design to extend the Roman will to the New World couldn’t triumph over a pre-European indigenous spirit. Architecturally European the city may be, but a resilient native mood permeates its vast halls and corridors. The mixture of tangible European planning and intangible pre-Columbian spirit turned my tour into a multicultural experience; it bestowed on the nation’s capital a mestizaje that will become even more pronounced as the population grows more diversified and people from non-Western traditions project their own sensibilities on this grand, ceremonial city.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.