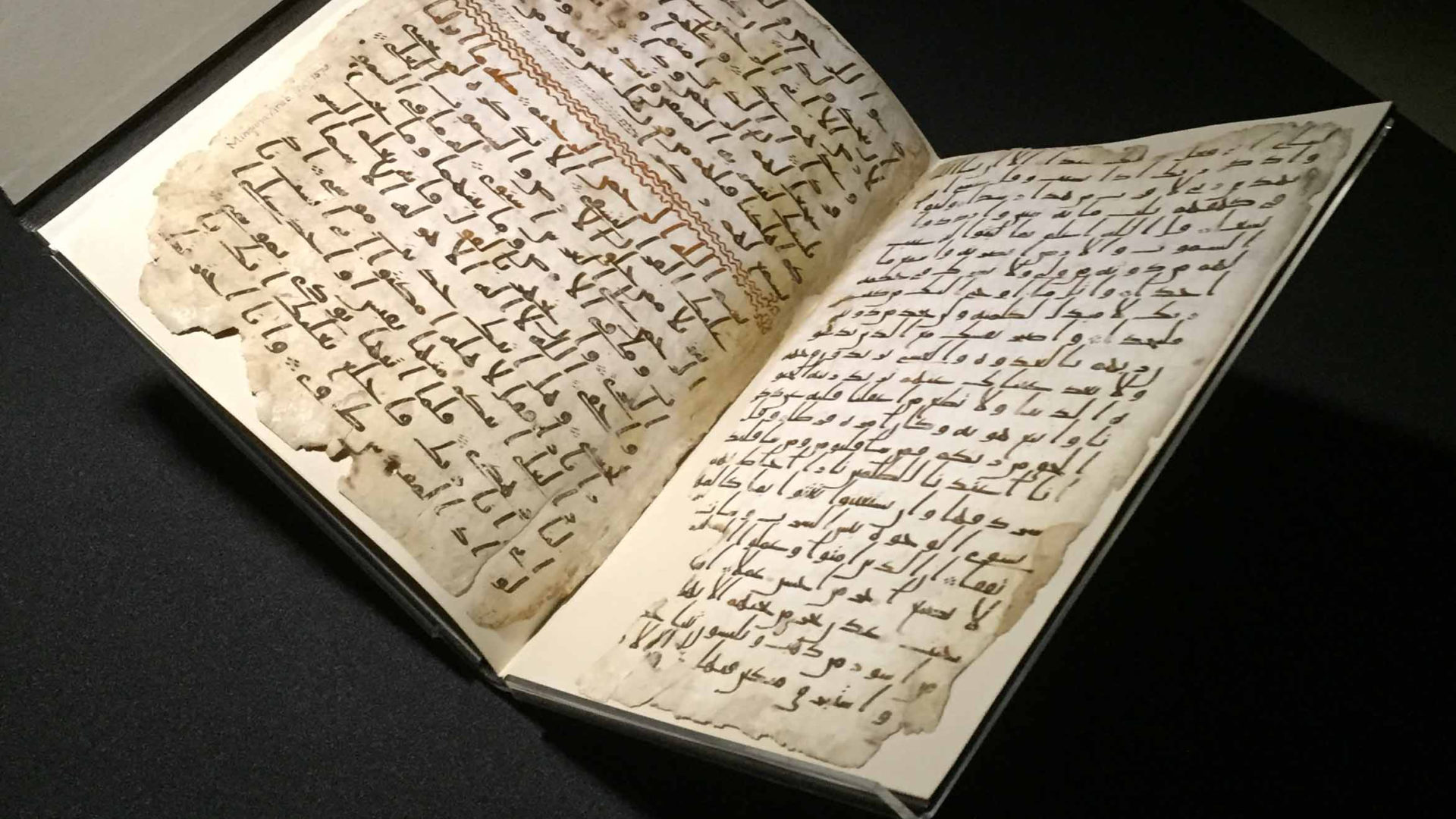

The recent discovery of fragments of a Koran dating back to the early decades of Islam was major news around the world and a source of great excitement to Muslims everywhere. Carbon-dated with more than 95 percent accuracy, the fragments, housed in the Mingana Collection of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Birmingham, leave little doubt about their historical provenance.

But, what exactly is the significance of this revelation? Is this dating proof that the Koran is the actual and unaltered word of God, as Muslims believe? Or does it show the ways in which the holy book evolved over time until it reached us in its present format? Alphonse Mingana, the intrepid manuscript collector who found the documents and brought them to England, believed the latter. He knew that he was in the presence of early specimens of the Koran, but such knowledge was consistent with his overarching analysis of how the Koran was written over time.

According to official Islamic tradition, the Koran was assembled by the caliph Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644 – 656), when news of the existence of several versions of the Koran came to his attention. The Prophet Mohammed’s scribe, Zayd ibn Thabit, had already written one commissioned by the Caliph Abu Bakr, the immediate successor to the Prophet; but apparently this early collection, gathered from fragments inscribed on date leaves, strips of vellum, potsherds, and from the “hearts of men,” was not sufficient, or had given rise to other readings, reflecting, perhaps, the many dialects of the Arabic language in the region. So Calpih Uthman asked the same Zayd to head a small committee and do the work all over again. Once that task was completed, Uthman sent copies of this new authoritative edition to the four corners of the expanding Muslim empire and destroyed all previous copies. This is why Uthman was designated by his enemies as “the tearer of the Books.” He had “found the Qurâns many and left one,” says an account about him.

The parchment leaves found in Birmingham could, therefore, be either from a surviving pre-Uthmanic version that escaped destruction or from a copy of Uthman’s authorized Koran.

In the end, news of the Birmingham Koran does not, in any way, change our understanding of Muslim history. The major questions we have about the authorship and meaning of the Koran remain unexplored because this discovery alone leaves us in the same perplexing place of Muslims who first read these early versions of the Koran. Without vowels and historical context, they couldn’t make much sense of the actual text. That’s why the fragments of Birmingham were the beginning of the making of the Koran, not the Koran’s final message. If it’s easier to read the unmarked text today, it’s probably because its meaning has long been established, and so we are reading backward, as one, in fact, does with an aide mémoire.

No one was more clearheaded about the history of the Koran than Mingana, who was born in northern Iraq. He knew that Mohammed, during the time of his mission, from 610 to 632, was too busy with wars and nation building to remember every exact message revealed to him in those years. In essays he published in 1914 and 1915, collected in Ibn Warraq’s Which Koran?, Mingana also reminds us of the well-known story of Zayd, who, when asked by the first caliph Abu Bakr to write down and arrange the Koran, resisted the offer, arguing that Mohammed himself had refused to do so. Zayd ended up compiling the Koran anyway—twice, as it happens–but this would not be the last time someone took editorial credit for the Muslim holy book. The Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik of Damascus and his lieutenant Hajjaj ibn Yussuf in Iraq (presumed to be the first Muslim to write on papyrus) are both credited by other sources with re-editing the Koran and drawing up the standard text, even though unauthorized versions, such as the one by Ibn Mas`ud, one of the Prophet’s companions, survived well into Abbasid times. Such copies, when found, were burned, and sometimes their holders were flogged.

It is, in fact, fair to say that the Koran came into full maturity during the Abbasid period, when the vowel system, inspired by developments in Aramaic and Hebrew, was added to the Arabic script. The grammarians of Iraq invented the hamza, too, while Christian scholars, led by Hunain ibn Ishaq, translated Greek and Syriac texts into Arabic. This was the period, when the canonical texts of Islam, such as the siras (biographies of the Prophet), hadith (compilations of the Prophet’s saying and doings) and the books of jurisprudence, were being developed to provide clear guidelines to Muslims and explain away the flagrant contradictions in the Koran, as when God asks Muslims to make war on unbelievers in one instance and be kind to them in another.

Proficient in Syriac, Arabic, French, Latin, Turkish, Persian, and Hebrew, Mingana lamented the lack of critical analysis among Muslim theologians—a remark that is valid today as it was a century ago. He knew very well that the Koran was inspired by Christian and Jewish ideas. Its composition in Arabic was, in a way, the coming of age of a group of people—the Arabs, also known as Hagarenes and Ishmaelites—who had long been viewed as violent brutes. The latter borrowed as much they could from neighboring Christians and Jews, but they committed a number of errors in the process, reflecting their tenuous understanding of these ancient and complex religions. For example, Miriam, the sister of Aaron in the Bible, is confused with the Virgin Mary. The names of John (Yohanna) and Jesus (Esho`) are given in the vulgar version (Yahya and `Isa) used by certain Christian communities. Mount Sinai is called “sineen” to rhyme with the rest of the verse. Equally confounding is how Saul and Enoch became Talut and Idriss. Finally, to say that the Jews believed that Ezra, as the Koran claims, is the son of God is a serious misrepresentation of Jewish scripture.

Alphonse Mingana’s reading of the Koran has yet to be given a proper airing by the Western media today. His views were at the cutting edge of research into the poorly understood history of early Islam, and his successors today are still laboring in the dark. To think that the Koran is a human composition is treated as an intolerable affront to Muslims, and so the topic is left alone. While Jews and Christians have long approached their histories of the composition of the Bible critically, Muslims still believe that the Koran is the uncorrupted word of God and, therefore, can never be disputed. Not only that, but Muslims never bother to study other religions because they believe that theirs is God’s final and best message.

To me, the Koranic fragments of Birmingham tell a different story, one that highlights the sorry state of Muslims today. Thanks to the financial support of an English Quaker (Dr. Edward Cadbury), a Christian Arab (Alphonse Mingana) was able to find, save and protect a precious part of the Muslim cultural heritage from the burning fires of hatred and zeal that are constantly consuming Arab and Muslim lands. This is but one example of how Christians, Jews and Westerners, through centuries of arduous work, have been indispensable for a better understanding of Islam and its history.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.