Abdelhay Mohammadi, lycéen . . .

apprenti kamikaze dans la commune

de Sidi Moumen . . .

Tous les jours après l’école,

Abdelhay se rend à la petite mosquée en tôle

ou il apprend à faire des tas de choses

formidables, et même de vraies bombes . . .

Abdelhay sait qu’un jour ou l’autre,

il passera à la télé.

Miniatures 46, Youssouf Amine Elalamy

Oh, Rose, thou art sick.

The invisible worm

That flies in the night

In the howling storm

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy,

And his dark secret

Does thy life destroy.

William Blake

“Thanks to you, I die like Jesus Christ,

to inspire generations of the weak and

the defenseless people.”

Cho Seung-Hui

The minute I got them home they began to expand. In the medina, tightly packed and deprived of water, they lay in forlorn bunches, piled into straight-jacketed uniformity.

“Une douzaine, madame?” the vendor smiles ingratiatingly.

Lifting shaggy stems, he rapidly scrapes thorns and leaves, his blade finally lopping diagonal tips. He holds the bouquet aloft, pivoting for my approval.

“C’est bon?”

I nod, and he bundles the bunch into green paper securing it with a red ribbon.

“Et, voila!”

The fleshly petals, compacted into whorls, gradually open to reveal the delicate erect pistil, its drop of sticky moisture quivering. Some are labial pink, deepening to a coral center, others pulse with red velvet and copper, the colors of the taste of blood.

In only three days the roses are full blown.

* * *

That Saturday morning, I knew something was wrong. As we step out of the petit taxi, the blue iron gates of the Rabat American School are clamped shut. Side streets strangely deserted, a bristling row of orange traffic cones bars the curbside.

“Baseball, sidi?” I ask the guard, puzzled.

“Non, madame, pas aujourd’hui,” not today.

But Ibby’s Astros were to play the Pirates in a double header and we had even brought juice and potato chips. Then I see the hand-printed sign: SCHOOL CLOSED REGRET INCONVENIENCE. Neatly choreographed knots of armed policemen dot the perimeter; the nape of my neck tingles with apprehension. Suddenly, I know.

Here in Morocco they call them kamikazes, the mostly illiterate young men from the bidonville Sidi Moumen, the notorious sprawling slum crouching just outside the gleaming glass towers of Casablanca. This latest incident was preceded by another, four days earlier, when cops raided the hideout of four kamikazes, three of whom detonated themselves, and it is also a stepchild of the Casa cyberbomber. A month ago, prevented from accessing a radical Muslim internet site blocked by websnoops from Moroccan security, a volatile youth first harangued the café owner–and then just blew.

Saturday’s episode occurred early in the morning on a graceful tree-lined boulevard near the American Language Center and US Consulate. Using a compound of acetone, the main ingredient in nail polish remover, three kamikazes detonated themselves, scattering fragments across the pavement in wavering patterns like the flickering shadows cast through tattered palms.

* * *

“We Moroccans are as shocked as anyone,” Lahcen, a university colleague, assures me on Monday, sounding just like Captain Renaud in Casablanca. “Shocked, just shocked. But we know the police are doing a terrific job, a wonderful job,” he repeats for emphasis.

My train home clicks past the fomenting bidonvilles around Salé, a world away from prosperous international Rabat on the other side of the Bouregreg River. Stretching for blocks, tin-and-plastic-roofed hovels are all capped with a parasitic “parabole” sucking out the living marrow beneath. Rusting miniature amphitheatres, they offer not the redemption of tragedy but only flat-roofed despair, existence reduced to the dead end of THINGS.

In Morocco’s highly charged political atmosphere, the ineptitude of these explosions—their casualties limited to only one bystander–highlights a symbolic rather than conspiratorial significance. Against an international background of war and unrest in the Arab world and framed by the upcoming legislative elections here where the PJD, the Islamist party, is expected to make major gains, these deafeningly silent film noir-ish Keystone Kamikases beg explanatory subtext. The press eagerly obliges.

Sighing, I open the International Herald Tribune. Predictably, it hypes the violence but unable to establish any link to Al Qaida can only infer a plot by relating Saturday’s explosion to others, to Algeria, finally to 9/11. The individuals who have committed suicide are journalistically obliterated, the very label “terrorist” immediately meshing, Velcro-like, onto our own fears to condemn en masse an entire culture. The westernized Moroccan Francophone press also revels in language like “PANIQUE” superimposed on a lurid montage of cops in urban battle fatigues, menacing black balaclavas and businesslike machine guns. The domestic message is clear: the government is fully in control and the Islamists discredited. A narrow sidebar identifies the dead; one was nicknamed “the rose.”

Beyond this murderous political calculus, the algorithms of loss and gain, a photograph that takes root in my mind and sits like a cold hard rock in my belly: the home, the parents of the cybercafé bomber, the rotund mother swathed in a bathrobe and headscarf, the father on his haunches in prayer posture, both intently staring at the only vista in this windowless stone-walled cell: an enormous television. The television screen looms over the small figures in the foreground, skewing even further an incomprehensibly claustrophobic perspective. The size of an oblong closet, this bare moldering mausoleum has walled up alive an entire family of people who eat, pray, quarrel, make love, and sleep here. Illiterate, unemployed, and sexually repressed, the only outlet for a seething magma of frustration is not just the ideology he absorbs from the imam or Al Jazeera–but simply UP.

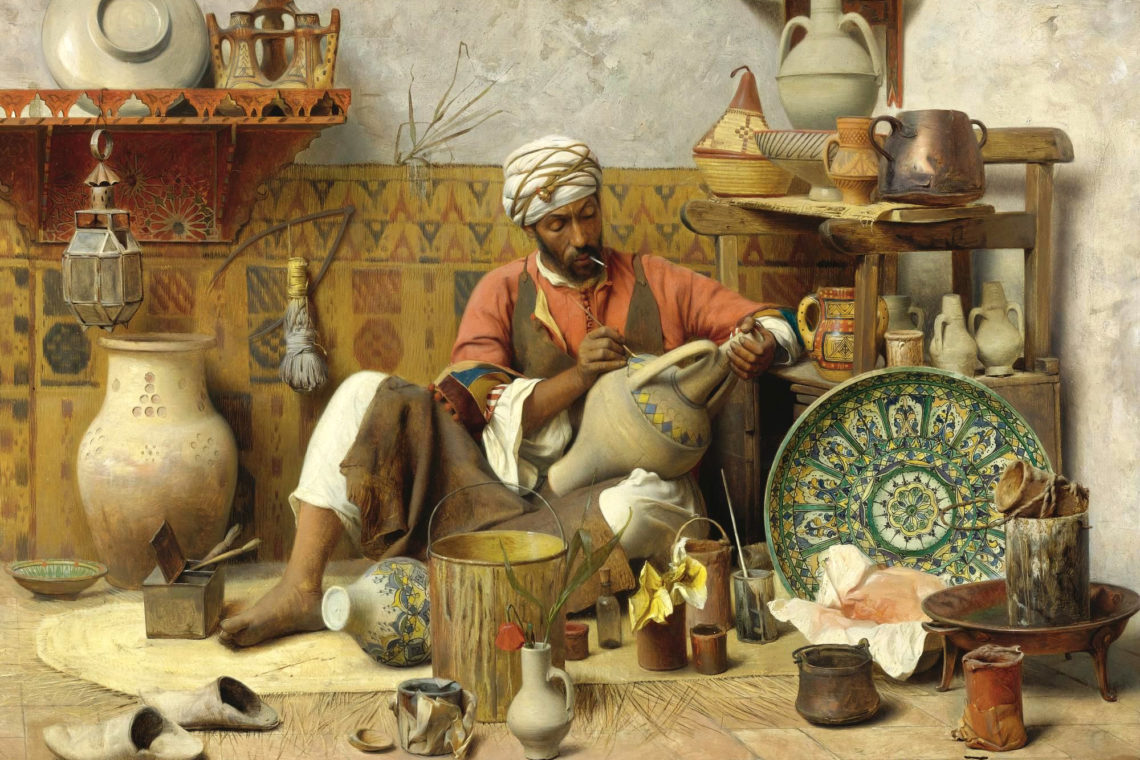

There is only UP because here there is no horizon, no wave-rippled shore beckoning across the Straits of Gibraltar to Europe, no books to inspire the alternative universe of imagination or situate the self within the landscape of human history; artisanal skills lost in this urban wasteland, no expectation of employment; there is only UP—POW! Self-immolation to evade the confining skin of the hopeless isolate self unable to enter into the body of another like the lapped petals of the rose enclosing the flesh in an embrace of lover of fetus in the womb, of the infinity of human generation: no, only the present expanding into a timeless unbearable tension that —

* * *

I am always amazed when survivors are able to talk in complete sentences but, mostly, that they are still normal in appearance and not, like a Picasso “Guernica,” jagged fragments with exclamation-pointed fingers and eyes staring like sprung watchsprings.

One survivor related quite coherently what had happened: the first time he was shot in the shoulder and decided to play dead; but when the killer returned, systematically quartering the rows of desks, he felt a sting in his thigh, then another bullet thudded into his buttocks. He said he tried not to move. Few moved. Some did jump out the window, others heroically tried to block the door, but most were transfixed and most died. He was so organized, so methodical, so effective. Although his hapless actors might be unsure of their lines, here at least he could be confident; he knew the script: like Borat, he had written it himself. And it was all about UP.

No “terrorist” from Sidi Moumen, this “troubled youth” was an upwardly mobile South Korean immigrant from his parents’ $400,000 home in lush green Chantilly, a suburb bordering blue-blooded Virginia hunt country. A sister is at Princeton. She is studying economics. But in America he remained a loser, an English major at a state university known for its topnotch engineering program. By the measure of a competitive Protestant ethic which decrees “just do it” and sees salvation reflected in salary scale, he was one of the unredeemed. A disappointment to his family, he wrote plays so envenomed his professors alerted the police who, unable to read text, dismissed these scenarios as mere “fiction.” The poet Nikki Giovanni, more clearly understanding the power of words, put her career on the line by refusing to teach this apprentice. Lexically precise, she spelled out the euphemism. Not “troubled youth,” she insisted: “He was mean.”

In a long feature, Newsweek eschews the term “terrorist” to dissect “The Mind of a Killer,” trying to medicalize madness, seeking Western scientific rationale in case studies and statistics. It locates the self-destructive worm in a gene that “planted an evil seed,” sees it nourished by the hothouse pressures of American immigrant expectation to finally curl around the trigger to blow away 32 people.

A photo of this –killer, kamikaze, terrorist, troubled youth, murderer, maniac, mean –covers two pages of the magazine, a blow up smugly supplied by the artist. After filming himself in iconic TV gangsta rap poses, he had paused between cuts to mail NBC News advance rushes of his starring video. The ultimate theatre of the real, this grand guignol of aggrieved martyrdom moves between illusion and reality, word and deed, image and language, allusion and acting, in a realm where the apprentice’s access to webcams, recorders, cell phone cameras, IM, blogs, facebooks, MySpace identities, and cut and paste do-it-yourself YouTube shorts all aid in constructing the ego of an American Dream blown out of all proportion. Cho was indeed a loner; sure, he was even a nutzoid—but he was no loser. Unlike the Casa Keystone Kamikases, ultimately Cho got it: a 21st century entrepreneur, he understood that America is really all about virtual UP.

* * *

The other night at a literary soirée set in a gorgeous Arab riad, I chatted with Tarik, a distinguished Moroccan political analyst. Underneath the stars, surrounded by Moorish tiles and fret worked plaster blooms, next to the courtyard fountain floating with rose petals, we sipped tiny golden glasses of the ubiquitous Moroccan mint tea.

“Ah, yes, the Blacksburg killer,” Tarik nodded. “Can you imagine if he had been Muslim? Oh là, là,” he gestured in the air, paused: “Not one report mentioned his religion.”

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.