Our apartment has—how shall I say this delicately?—a smell. The odor emanating from the wool blankets I recently bought in Tangier permeates our rooms and lends them the rich aromatic depth of an animal’s den. As I walk up to the roof terrace, I notice whole sheepskins draped along the railing and a washerwoman diligently cleaning thick Berber carpets. On the boulevards of fashionable Agdal where we live, young men have taken to wearing smart leather, girls tight jean jackets, while in the medina old men now squat quietly in heavy wool felt djellabas. For it is time: the cool rains have begun to arrive from the north with spongy gray clouds, at night glistening the pavingstones of Rue Ibn Hajar and bending the palms in the municipal gardens. Yes, time to think seriously about covering, both for our home and ourselves.

In summer, when we arrived, this was simple enough, for we had brought cotton and linen and at first were concerned merely with points of etiquette: adapting our Western style by covering knees and shoulders, making sure one’s derriere was disguised. I even noted with patronizing compassion the Moroccan women wearing headscarves and djellabas with the distinctive pointed hood, the haik, that transformed them into tall Christmas elves, weirdly inverting the season. The allure of the flowing fabric nevertheless gradually pulled me into the souqs of the medina, but the cheap spangled nylon and frogged rayon were mere caricatures of the intricate beauty of Arab dress. I did find a few linen pieces remaining at the end of summer and bought two long heavily embroidered tunics with matching narrow oriental trousers and, completing this elongated line, tasseled babouches, soft Moroccan leather slippers. But my thin necklaces and polite earrings now appeared insipid against the heft and drape of the cloth. Idly, I took up Ibby’s tin dagger and tucked it into my sash—voila! Suddenly, all was in alignment, all was ease and comfort, with the special delight that comes from knowing oneself well and appropriately dressed. African-like, by donning the mask, the skin, of my familiar, I had mysteriously entered into its spirit.

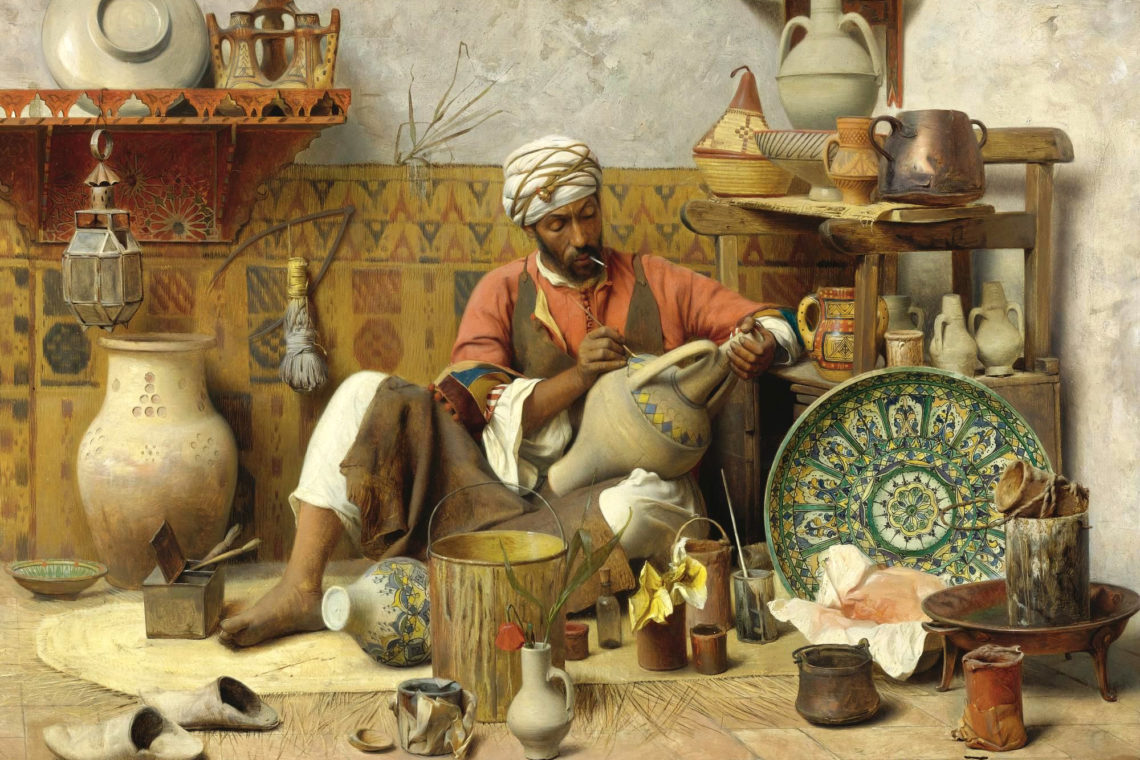

In a reverse of the biblical, I now realized that self-awareness derives not from nakedness, but rather from the selection of our covering; and animal skins, fabrics, and grasses all serve as both group and individual forms of shelter. Seen in this light, the pageant of traditional Moroccan couture emerges as variations on the tent: shelter adapted into clothing. It situates the individual against a rich background lent by ancient patterns of home, protection, sanctity. What else are the billowing skirts of the djellabas and their long open tunics but allusions to the flaps of tents in a high desert wind; and, by extension, women’s covering, often reviled in the West, but a living reference to the veiled entrance to Paradise, making of her a vivid metaphor of refuge and her penetration an analogy to spiritual awe. In his robes, soft slippers, and jeweled dagger, the male is transformed into a moveable feast of protection, of hospitality, striding or lounging within a volume of cloth so much more abundant than the meager form of his body. Berber women are especially obvious examples with their sturdy bright red-and-white striped skirts and enormous palm hats, mimicking a joyous adaptation of tree-and-tent. And it is also no small consideration to realize that these garments shield their wearers from very real dangers of sun and cold, while dispensing with such fussy acoutrements as Western caps, sunglasses, gloves, or even shoelaces.

Stifling a pang of regret for a haik or headscarf as I wearily anticipate the ritual of preparing my hair for the day, I reflect that our Western emphasis on individuality with its attendant range of sartorial options has often failed to embody an organic connection to landscape, to a wider social cohesion, to a sense of ourselves as havens and repositories of the intricate fabric housing our humanity. At present, Moroccans have the option of jeans and a baseball cap and the djellaba and headscarf, each a profound choice. As I feel the October sea wind ruffling my skin and crawl under my wool blanket, inhaling its comforting animal scent, I am all too aware of my forlorn nakedness; and understand that at times we must take group shelter, huddling in a hide more expansive, more nurturing, and more durable than our own.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.