I usually stride briskly down Rue Ibn Hajar. And always with eyes averted. But, today, as I scan the solidly male clientele lolling outside La Bonne Galette café, my eyes inadvertently catch those of a young man: contact. Immediately, I look down, focus on his feet in striped soccer shoes. Adidas. Notice his jeans, saggy at the knees. Coffee glass poised in midair, he imperceptibly tenses his shoulders. I increase my pace but risk one more quick upward survey. Too late.

“Ça va?” he croons. “Ah!” he murmurs, “gazelle,” and places his right hand over his heart.

Resisting an impulse to flip this guy a real bird, I train my eyes myopically toward the middle distance and stalk past.

And nearly collide with an old countrywoman in niqab, a black face veil. Her enormous bottom working under a thick djellaba, she waddles on square feet wedged into pointed mules, her bare orange-hennaed heels flapping. He doesn’t give her a glance, his eyes still riveted to my uncovered blonde head.

At the corner of Avenue de la Victoire, a red light.

A chic, middle-class woman clicks by in stiletto boots, briefcase swinging, her Muslim headscarf, the hijab, neatly pinned with a jeweled brooch. His eyes continue to bore holes through my thin skin.

A uniformed policewoman blows her shrill traffic whistle. Giggling schoolgirls, arms locked in protective phalanx, sway suggestively across the street in stovepipe jeans and bare midriffs above buttocks hard and round as Persian melons, sunlight reflecting the red-gold strands in their sinuous, long black hair. He turns, grins appreciatively, quickly shaking his hand down from the wrist: hot.

“Fitna,” he exclaims.

Chaos.

* * *

Fitna, chaos, slang for a pretty girl, anciently meant primal upheaval and more recently the social disorder evoked by a desirable woman. The glorious profusion of Moroccan women’s heavy glossy hair is the very energy of life, a cascade surging and powerful. Its sensuous beauty is indeed seductive, and in a repressive culture very, very dangerous. In Morocco, as in much of the Arab-Muslim world, women’s chastity is the foundation of social order—and female growing, flowing hair a force that may annihilate a man’s control, collapsing the great pillars upholding his temple into mere rubble. Since in Islam, as in most patriarchal cultures, women are human tokens bartered in the never-ending negotiations of masculine one-upmanship, it becomes important to clearly designate the virtuous—those whose progeny is stamped with the legitimate coinage of self-image—from the counterfeiters who commit zina, fornication. Morocco is a moderate Muslim state, but on the streets of even cosmopolitan Rabat, women without hijab are still fair game for lounge lizards.

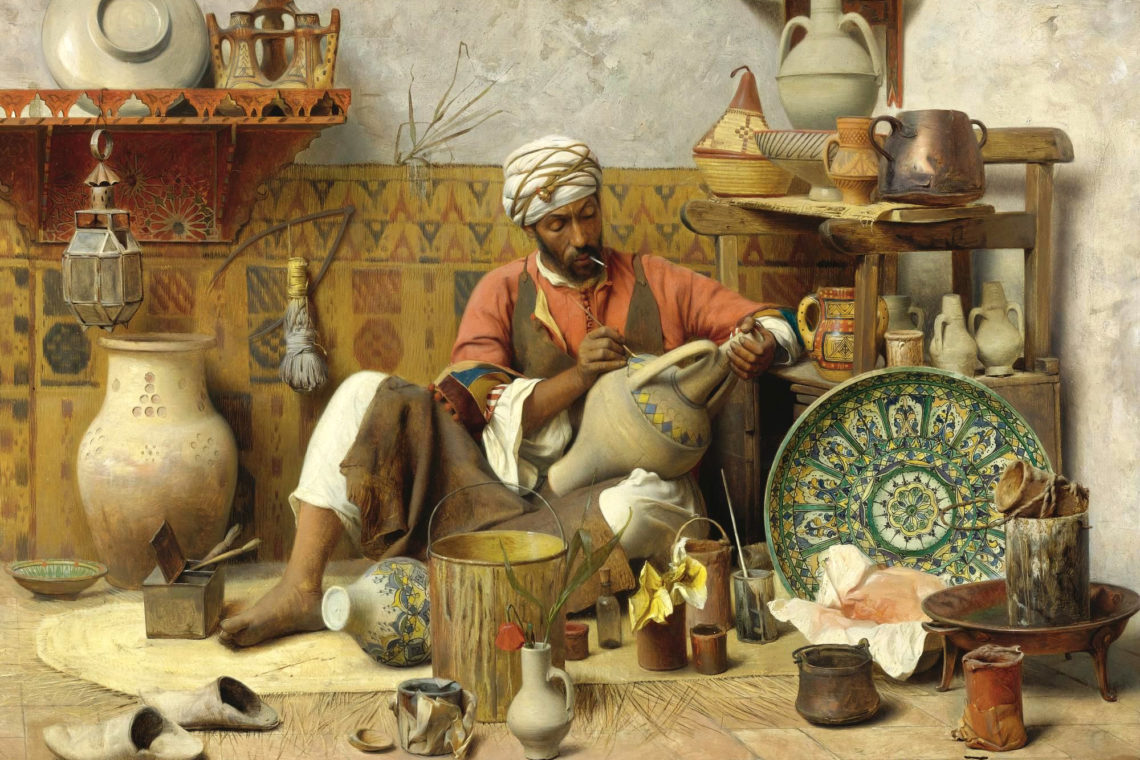

From tonsured monks, rabbinical curls and Rasta dreadlocks, to patriarchal beards and Ninja plaits, males have reserved their own hair as overt signs of spiritual allegiance and social standing, while squashing female tresses under veils, wimples, snoods, polite hats, or the ubiquitous Mediterranean black scarf—all headgear denoting feminine piety and propriety. In the Christian West, men uncover their heads indoors, and it is considered the height of sacrilege to wear a hat in church. In Islamic Morocco, however, devout men sometimes wear head covering; a rural man might wrap his head in a turban, another dons a small white embroidered cap, when going to the mosque. Occasionally, you may even see the red “flower pot,” the tarbush, but this usually signifies subservience catering to the tourist trade—a self-mocking rug merchant, perhaps, or an obsequious doorman. In general, the cultural flashpoint for both East and West has always remained hair, especially women’s hair.

My would-be swain checking out the action from his sidewalk perch at La Bonne Galette represents over a thousand years of social conditioning in a culture where Muslim males controlled all public spaces from cafés and corner stores to realms of commerce and councils of state. Women inhabited a domestic sphere where they reigned supreme in the sequestered household. For a woman to trespass into male territory, she had to literally tie her body to a flag of truce: the hijab.

In the classic film It Happened One Night, Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert are stranded and forced to spend the night together. Unmarried, they resolve their awkward faux connubiality by stringing up a sheet between them. In colonial New England, courting couples would “bundle,” snuggle together in a warm bed—on either side of a stout board. Hijab means curtain, or barrier, and it functions much like Gable and Colbert’s sheet or the New England bundling board: to at once intensify sexual awareness while bracketing man from woman. In 7th-century Arabia, males in Medina could easily identify the Prophet Mohammed’s wives by a distinctive head covering that marked them as out of bounds. After Mohammed’s death, hijab, like a submerged shard of ancient pottery, gradually accumulated the hoary, often misogynistic barnacles of hadith, apocryphal sayings attributed to the Prophet, and by the 8th century, hijab came to denote the incisive gender segregation that finally cleft the Arab-Muslim space in two.

In the 1950s, Sultan Mohammed V, father of the new Moroccan nation, declared the veil obsolete, pointing with pride to Princess Lalla Aisha, his lively daughter who boldly appeared on the public stage without the traditional niqab or even hijab. Immediately, lines were drawn, not in any metaphorical sand but on the very terrain of women’s bodies, and, today, the decision to wear the headscarf–to “do hijab” or not—remains basic to every Moroccan woman’s social role and cultural identity. In global mass media, hijab has become the locus of vituperative debate, the nexus of reciprocal East-West finger pointing, and a political weapon pointed squarely at the heart of vaunted Western “multiculturalism.”

The ardent Moroccan feminist and Muslim sociologist Fatema Mernissi argues passionately that hijab has been misconstrued. As she sees it in her brilliant book The Veil and the Male Elite, hijab is not to be taken literally; on the contrary, as used in sura 53 of the Koran, it denotes an inner, spiritual boundary delineating individual space and hence emphasizing mutual self-restraint. She dismisses the literal practice of veiling women as a misogynistic vestige of pre-Islamic tribalism based in atavistic fears of female power. Her vision of Islam as a religion of individual dignity and gender equality—and her hard-headed itjihad, revisionist interpretation of scripture–offers a bridge into a Muslim future where women can regain their forfeited position as equal partners in the umma, the world-wide community of Islam.

Other, younger, politically outspoken Muslim women disagree with Mernissi and, adhering to a gendered “separate but equal” approach, assert their right to hijab as a sign of spiritual faith and proud cultural identity. They bristle at Western stereotypes of a weak and oppressed Muslim woman “forced” to wear the veil. The cover of the November 27 international Newsweek is a case in point. It features the usual Western male fantasy of a young beauty, large kohl-rimmed eye gazing vacantly, lush pink lips a startling focus of color against white face framed by black hijab. Even more predictably, letters enticingly promise: “BEHIND THE VEIL.” Such salacious Western images manage to offend nearly every woman–veiled or unveiled–here in Morocco.

The November issue of the popular Moroccan francophone women’s magazine Femmes du Maroc takes a more nuanced stance: “Phénomène Paradoxal hijab!” While hijab may be political banner and/or badge of cultural identity, it may also signal marital availability by young women in search of a respectable meal ticket in a country with high unemployment and low rates of female literacy. And, as the Moroccan socio-linguist Fatima Sadiqi, a visiting scholar at Harvard this year, has argued in several recent articles, hijab may even subvert traditional masculine spaces by lending women professional legitimacy. After the conservative backlash throughout the Arab-Islamic world following the Iranian revolution, paradoxically those feminists who wear hijab have emerged as effective advocates for human rights since they are more credible to their public. For Sadiqi, far from being a cocoon of oppression as the West would like to believe, in Morocco hijab has often liberated women.

* * *

“Hmmm,” I think, gazing around my university classroom. Perhaps Sadiqi is right. Perhaps the hijab is indeed empowering, as my assertive student Aisha seems to attest. Her hand is always raised and she freely contradicts the men in the class. Perhaps it’s merely holiday malaise, but I remain skeptical.

Here comes Laila, late as usual. Hiding her keen mind under a low-browed hijab that emphasizes her enormous eyes, sashaying on spike heels toward her desk, her ample curves poured into a (could it be?) slip over designer jeans, she is bound more tightly than a mummy.

Yes, it must be the holiday spirit. . .

Last night I wearily asked my twelve-year-old son if I had to wrap all, really all, of his presents?

“But, mom! It’s more fun to open them if they’re, like, wrapped!”

* * *

Merry Christmas.

Eid mubarak.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.