As an Anglo-Irish American raised on visions of Africa, it took a scholarly conference in Marrakech this past year to bring me to Morocco. By that time, I had lived in three sub-Saharan African countries, but had yet to visit the Maghreb.

My parents lived in West Africa before I was born, and a picture of my mother dancing with the foreign minister on Liberian Independence Day was iconic in my childhood. My godfather Dismas Mdachi, a Tanzanian educator and family friend, twice visited our home in America and urged me to come to his country one day. My maternal grandfather, a New Englander born in Alexandria, spoke of Egypt as if it were outside of Africa, and yet he also nurtured my African dreams. At 20, I set forth on my first African adventure to Kenya, where I studied East African literature and politics, lived with a Luhya family and explored the Swahili coast. My next trip ten years later brought me to Conakry, Guinea, and a United Nations post working with Liberian refugees. My Guinean and Liberian colleagues and neighbors were mostly Muslim. Islam pervaded my experience, and for me its presence was both subtle and tolerant, not unlike the universalist strain of Christianity woven through my own Massachusetts upbringing.

Four years ago, a mother of two and a professor of human rights law, I traveled to Tanzania where I taught international law at the University of Dar es Salaam, and conducted fieldwork in the Burundian refugee camps in the western part of the country. The Mdachi family welcomed me, along with many new Tanzanian friends, both Muslim and Christian. I was inspired by the legacy of Nyerere and his vision of African socialism, the nation’s strained yet enduring hospitality to refugees from the Great Lakes Region, and Zanzibar’s mosaic of African, Omani and Persian influences. Having experienced East and West Africa, my eyes looked northward.

This past autumn, encouraged by a friend from Tangier, I planned my first excursion to Morocco, about which I knew little. In November 2006, I participated in a conference in Marrakech, where former and current Fulbright scholars from Morocco, the U.S. and elsewhere gathered, to address cross-cultural perspectives on education, economic development and human rights.

My impressions from seven days in Marrakech are varied and somewhat fleeting. Newly arrived in the city, I felt a bit strange yet secure walking through Bab El Makhzen into the Medina and the souks around Place Jemaa el-Fna. We American human rights scholars can get somewhat fixated on the subject of the veiling of women in the Islamic world. Sartorially speaking, what impressed me most strolling through Marrakech’s Old City was the great variety of head coverings and lack thereof for women and men alike. I saw some women in headscarves and long robes, both plain and multi-colored, others wearing scarves and Western-style dresses, and others still with uncovered heads and slacks. I watched Gnaoua musicians performing and dancing in embroidered caps and jellabas, and noticed other hatless men in Western clothes, and even one in jeans and a baseball cap. Amidst the sellers, shoppers, locals and tourists, my own unveiled head attracted little notice. But by far the most visually stunning aspect of Marrakech was the minaret of the Koutoubia Mosque, a constant handsome landmark from a distance, and a serene and humbling presence in more intimate proximity.

Later in the week, I attended a panel discussion during the Fulbright conference on the Moroccan family code, in particular recent amendments to the Mudawana, serving to increase the rights of women in divorce and raise the minimum age for marriage. Both Moroccan and American panelists emphasized the challenges in implementing these changes, given a wide variance in enforcement by judges at the local level. Moreover, ongoing support by the monarchy for enhanced legal protections for women will need to occur within a dynamic political context characterized by increasingly active civil society organizations and Islamic and more secular political parties with potentially divergent agendas.

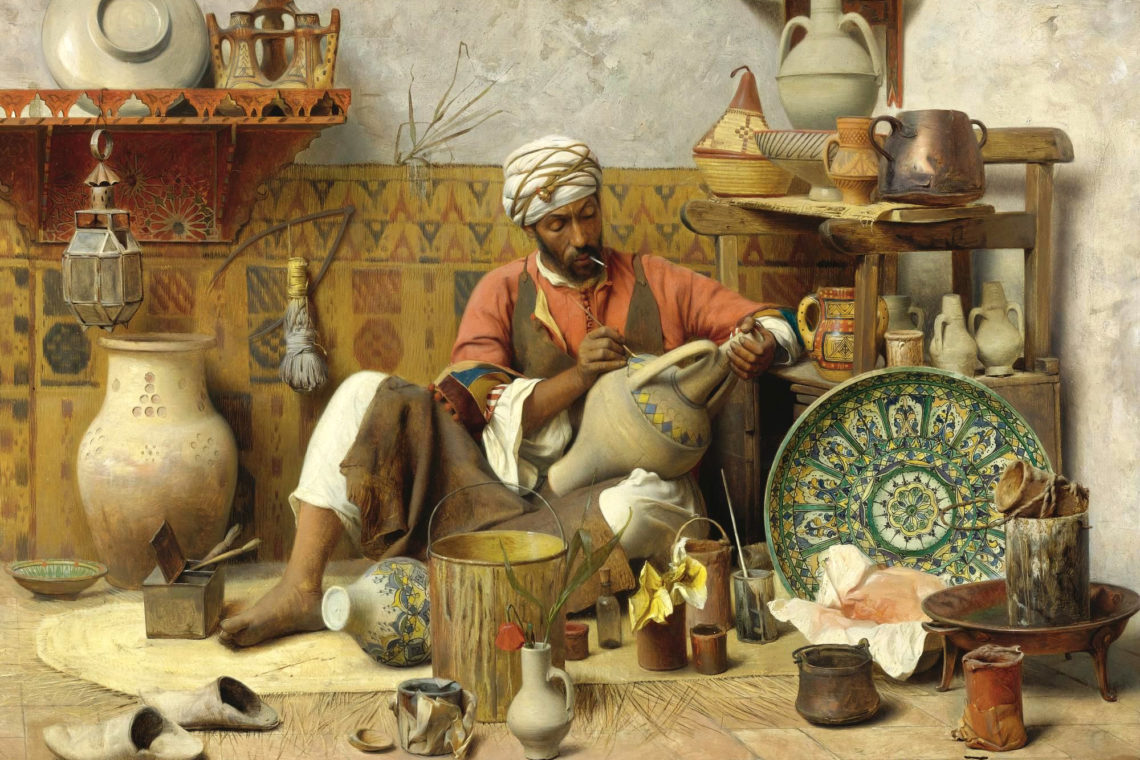

My limited reading of Moroccan history before traveling to Marrakech highlighted the cultural, religious, agricultural and architectural cross-fertilization between Andalusian Spain and Morocco between the 8th and 15th centuries. Some of this cultural legacy is also evident in New Mexico, the state in which I reside, in the Moorish influences in colonial Spanish architecture and the acequia irrigation systems still used today by farmers in northern New Mexico. As I toured one of the old palaces of Marrakech, my eyes were drawn up along the walls of the interior rooms – colorful geometric ceramic mosaic tiles beginning at floor level, topped by panels of intricately carved and painted plaster, leading to warmly-hued ceilings of cedar-wood mosaic.

On the plane trip to Marrakech from Albuquerque through Chicago and Madrid, I had also read about the historical roots of the Gnaoua musicians of Morocco, and their descendence from West Africans enslaved to serve as palace guards for Sultans Moulay Ismail and Moulay Abdallah during the 17th and 18th centuries. While in Marrakech I watched and listened to Gnaoua performances, one in Place Jemaa el-Fna at dusk and another at night outside a restored palace, the musicians illuminated by moonlight and the soft glow of lanterns. Citizen of a country that enslaved Africans less than 150 years ago, I marveled at being in the presence of Moroccan descendents of West Africans, hailing long ago from a part of Africa that had also nourished me.

While one week at an academic meeting could only provide me with a taste of Moroccan culture, two impressions from my trip to Marrakech remain strongest. To begin with, Morocco is indeed a part of Africa, just as Morocco, through Andalusian Spain, transported African culture into Europe. I am also convinced that by visiting and learning about Moroccan society, we Americans may gain deeper insights into the challenging, dynamic and promising relationship that exists between Islam, Africa and the West in the world today.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.